JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

“Hey Santa!”

The music video for George Michael’s “Outside.”

Like a funny version of John Greyson’s Urinal (1988).

A typical porn theater.

“Tearooms and Sympathy, or, The Epistemology of the Water Closet.”

Clinical imagery during his discussion of AIDS.

An archaeology of medical perception.

Sexual space: trucks.

Sexual space: porn theaters.

Fenced Out.

Hudson River Park Trust.

A privileged moment of documentary truth: “Turn that off.”

DESTROYER.

A crowd sunning themselves on the pier.

Photo of the crumbling old pier in Fenced Out (Gay Sex in the 70s is also replete with such photos).

Another strangely beautiful image of precarious girders.

Regina Shavers laughing at the question “Were there many public spaces for lesbian women of color?”

“New York’s not even the same.” (Paris Is Burning).

Willi Ninja (Mother of the House of Ninja) in Fenced Out.

The epilogue of Paris Is Burning.

The end of Fenced Out.

In The Polymath, Delany frankly states,

“I think that heterosexual monogamy is a really vicious and silly way to live.”

Since he has seen so many made miserable by it, he does not therefore “agree with it.” But he compares it to a religious choice, and thus he respects it the way one must have respect for other religions. By contrast, Delany explains in both The Polymath and Times Square that his ideal sex life involves

“a single person in my life as a sexual focus, at the same time a general population of encounters with different men (of the sort I’ve been describing here), along with a healthy masturbatory life. But what made that a feasible way to live between 1975 and 1995 were institutions such as the sex movies” (83).

He informs us that he actually does quite well for himself even in his sixties, since there seems to be a sizable number of younger men who are attracted to men with white beards (in the film we see a young African-American woman greeting Delany on the street with “Hey Santa!”). He also jokingly makes a double-entendre linking alimentary and sexual taste: as the “kinkier” black sheep of his family, he always “ate whatever was put in front of me” and seems to be pretty “well padded out” as a result. This analogy was also made by George Michael, who justified his “lewd behavior” when he was the victim of a sting operation in a Beverly Hills public park toilet by saying that he has “never been able to turn down a free meal.” (His video for “Outside” is a brilliant response to the whole scandal, and its satire of vice police panopticism is as refreshing as the work of Delany, Gayle Rubin, and Pat Califia. The scandal and “knowingness” surrounding Senator Craig’s recent Minneapolis airport restroom incident is proof of our collective amnesia [cf. Kim, “Brokeback GOP”].)

|

|

| A public toilet… | … becomes a disco. |

Clearly, this is where we see the “Opinions” part of the film’s alternate title (itself borrowed from Tristram Shandy). But perhaps this risks becoming too much of a gay versus straight polemic.

In an interview “Sexual Choice, Sexual Act,” Michel Foucault attempts to historicize gay male promiscuity, arguing that it has to do with the sexual freedom which men in general are allowed (prostitution, bathhouses, etc.), which means that opportunities for sexual encounters are enormous, and ironically

“by a curious twist often typical of such strategies—it actually reversed the standards in such a way that homosexuals came to enjoy even more freedom in their physical relations than heterosexuals” (326–27).

But Foucault insists that this is not a natural condition of homosexuality (a biological given), but is rather an artifact of history (327).

Following the interviewer’s prompt, Foucault argues that the “erotic imagination” and literature of homosexuality are likewise different from that of heterosexuals. In the case of heterosexuality, a great emphasis is placed on courtship, which is highly evolved and coded, and the persuasion involved in getting the beloved to surrender. By contrast, in the case of the homosexual “trick,” sex is given at the outset, so there is an elaboration of the sexual act itself (both its description and its practice), which is especially “coded” in the case of SM practices (330–31). Foucault notes that this was not always the case: for the ancient Greeks, homosexual courtship was central, and the problem of a male submitting to another was very important. But in contemporary homosexual experience, the act itself is easy to come by and so other things than the “lead up” to sex get eroticized. In contrast to Casanova’s famous expression, “The best moment of love is when one is climbing the stairs,” Foucault proposes, “For a homosexual, the best moment of love is likely to be when the lover leaves in the taxi” (330). He suggests,

"This is why the great homosexual writers of our culture (Cocteau, Genet, Burroughs) can write so elegantly about the sexual act itself, because the homosexual imagination is for the most part concerned with reminiscing about the act rather than anticipating it. And, as I said earlier, this is all due to very concrete and practical considerations and says nothing about the intrinsic nature of homosexuality." (330)

Delany’s own sexual reminiscences in Motion and Times Square provide excellent examples of the elaboration of highly codified sexual encounters. And while they fit Foucault’s schema above, Delany often insists that he does not want seem nostalgic (Times 16; 146–47; 166; Motion 294; de Villiers, “Leaving the Cinema”).

Foucault suggests that gay sex acts are not really what disturb people, but that gay people might develop satisfying and different types of relationships other than those that have been institutionalized (332). This is an important reminder during the endless gay marriage debates, but in fact Delany’s works both attest to such possibilities and insist that the problem is the demolition of “institutions” that facilitated satisfying cross-class, cross-race, and cross-sexual relations such as the Times Square porn theaters. In The Polymath, Delany explains that he likes cities because of their diversity and believes that it is essential to talk to strangers.

Foucault’s interview and Delany’s books might also be productively compared to Barthes’s preface to Renaud Camus’ gay cruising novel Tricks. Barthes claims that in Tricks, the “social scene” and the act of cruising become more interesting than “banal” sexual practices: the alert, conversation, the other person first as a “type” (“That’s just my type”), finally emerging as a distinct “person,” which either increases or decreases desire (294). Barthes argues that each Trick is therefore unique and in-imitable: each person is revealed “lightly” (without psychologizing) in their clothing, accent, and setting (294). The character sketches in Delany’s Times Square follow precisely this pattern. But Barthes notes that this is a “virtual love” (294), because it is stopped short on each side by contract (something which is in the end far better than the obligatory heterosexual, “I’ll call you”). We could indeed ask: Is there a heterosexual equivalent to this? Why or why not? (How is gender involved? Within patriarchy, a promiscuous man is called a “stud,” whereas a woman who enjoys sex is a “slut” or a “freak”).

But Barthes then asks: Does the repetition in Tricks mean that it is a sad or failed quest? No, because each “trick” is presided over by a feeling of happiness and “Good Will” which is usually quite foreign to amorous relations (294). There is actually a very subtle ethics at work here, which is what a disapproving condemnation of homosexual promiscuity (not necessarily unsafe promiscuity) often seems to miss entirely. Delany’s Times Square is equally concerned with the ethics of public sex, and when he speaks about the porn theaters as “humane” spaces, he echoes Barthes’s description of “tricking” as hospitable, generous, and considerate. The Polymath begins with Delany explaining how after he was married in 1961, daily encounters with a dozen or so men in various public restrooms made his working day bearable. He does not think he ever could have written and published five novels between the ages of 19 and 23 “without the sexual generosity of the city” around him because the sex made the work bearable. He explains that this was pre-AIDS, but in the AIDS era, when Time Magazine starting talking about gay men “living life in the fast lane” with three hundred contacts a year, he figured out that he must have two- to three thousand contacts a year. He remarks,

“I don’t think people have a good idea of the sexual landscape they themselves are negotiating as they walk down the street.”

Of course, in the film Delany acknowledges that his position is controversial, and does not suggest that anyone follow his example (he is HIV negative and rarely uses a condom, but anal sex is not part of his sexual repertoire). A more extended discussion of gay men’s ambivalence or resistance toward “safe sex” discourse can be found in Michael Warner’s book The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life. Yet Delany also argues that the tests that need to be done on HIV transmission risks have not been done properly, and he calls the prevailing atmosphere of misinformation genocidal. This attitude is not necessarily “politically correct,” [1] [open endnotes in new window] but it dovetails with the concerns of another recent documentary, Gay Sex in the 70s.

Polyphasic

Here I would like to connect The Polymath to a larger group of documentaries and videos that discuss comparable issues: Gay Sex in the 70s, Fenced Out, and Paris Is Burning (Livingston, 1990). They each share a similar focus on queer historiography, especially of the various phases of (and threats to) New York City’s queer urban life.

Gay Sex in the 70s features interviews with (primarily white) men who fondly recall public sex in the trucks off the Henry Hudson Parkway and the crumbling Christopher Street pier. The rather wistful talking-heads style interviews are illustrated with period photographs, street footage, and vintage pornography (all set to a disco soundtrack, obviously). The film covers the period between the Stonewall riots (late June 1969) and the AIDS crisis, but unlike And the Band Played On (Spottiswoode, 1993), it crucially avoids the conclusion that the sexual revolution and freedom enjoyed by these men were directly responsible for the AIDS crisis. In fact it demonstrates that the kind of social collectivity represented by the baths was crucial for early AIDS activism and safe sex information outreach (Bronski). Delany also insists on this point after his description of sex in the trucks and baths in Motion (294).

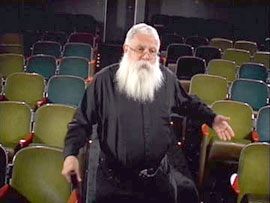

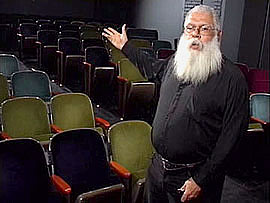

The Polymath shares another approach with Gay Sex in the 70s, namely the use of “guides” who recall in detail how exactly gay sexual spaces (baths, piers, trucks, theaters) were used. In a fascinating scene in The Polymath, Delany is filmed in a theater explaining what would go on in each row of a typical porn movie theater, starting at the back row, discussing the lighting, moving to the front, discussing the sexual acts performed, the etiquette of joining someone in a row, and the important guardian role of the queens gossiping in the back. This is an attempt to account for what de Certeau identified as “spatial practices”:

“these multiform, resistan[t], tricky and stubborn procedures that elude discipline without being outside the field in which it is exercised, and which should lead us to a theory of everyday practices, of lived space, of the disquieting familiarity of the city” (96).

In fact, Delany insists that far from being chaotic and anarchic, public sex is a highly choreographed and rule-governed social activity.

|

|

| Lighting and layout. | Delany as our helpful, knowledgeable guide. |

The Polymath and Gay Sex in the 70s are attempts to combat historical amnesia, especially the social and spatial amnesia brought about by AIDS and “redevelopment” projects. Delany does not “buy” any of the arguments about why the sexual landscape of New York City has been transformed: “family values,” “AIDS-prevention,” “love of theater,” “safety of women” (161). He argues that in demolishing the existing life of the Times Square area, corporations and investors have actually promoted crime, violence, drugs, and have shown a lack of respect or consideration for poor women (and prostitutes) in the interest of marketing to a wealthier group of women. A similar attempt to combat amnesia can be found in the short activist youth-produced documentary video Fenced Out.

Fenced Out features interviews with “Stonewall veterans” and young people about the Hudson River Park Trust’s attempt to fence out the poor and homeless gay and transgender youth of color who view the Christopher Street pier as the one place where they can go to feel comfortable and associate with those “in the life.”

In Fenced Out, a young woman’s voice reads aloud from the official version in a heavily ironic tone:

“Under the leadership of Governor Pataki and Mayor Giuliani, five miles of the riverfront from Battery Park to 59th Street is under construction to become Hudson River Park. It’s going to transformed into a ‘green and blue oasis’ for all of New York to enjoy.”

Another voice interjects, “Except for us, of course!” (“O.K.?!” another can be heard chiming in.) Several interviewees explain how law enforcement have gotten out of hand with their harassment of youth accused of loitering and lowering the property value of area residents. When the girl who started the documentary was arrested on the piers and asked the officer why, he replied,

“No offence to you, but these people don’t want you here anymore, and they pay our jobs, so we have to do what they want us to do.”

We then see a police officer condescendingly explaining the same point before he points to the camera and asks for it to be turned off (always a privileged moment of truth in documentaries). But in an interview with June Brown and Daris Jackson, it is clear that they will not stand for police telling them to “Shut up” and “Walk!” responding with the activist chant, “Whose streets? Our streets!”

Brown explains,

“The pier was a lot of good memories, a lot of broken memories, a lot of people died on the pier, a lot of people died for the pier. I think not only will it be bad for the future generations, but it will be disrespectful of the past generations to close down the pier.”

In his book No Future, Lee Edelman argues that invocations of future generations are almost always self-defeating for queers, but here Brown’s acknowledgement of past generations points to a refusal of the kind of infringement of civil liberties usually carried out in the name of innocent children. Fenced Out shows the youths interviewing older gay men and women about Stonewall and the Christopher Street pier. Bob Kohler explains that the Gay Liberation Front declared Christopher Street the gay street and

“that’s why you hear the cry today at demonstrations ‘Whose streets? Our streets!’ That came out of those days.”

Like the men interviewed in Gay Sex in the 70s, Kohler explains in Fenced Out how the crumbling piers were

“very unsafe, they were packed with people, walking up on girders, walking around naked or just having sex right in front of you.”

Ajamu Sankofa (N.Y.C. Police Watch) explains,

“People would hang out there nude almost, with food, fun, no police, it was as if we had taken that place over, and it’s sad to see years later coming back to it, it’s not the same place.”

One of video’s organizers, Corrina Wiggins, explains to Regina Shavers (Griot Circle):

“By doing this project, we went back and into like, the piers from like the 60s and the 70s and … we noticed that like the piers was mainly white gay males, and that led us to believe, like, we started asking questions: Where are the women? Where are all the women of color and the men of color?”

Shavers responds, “What I know about the piers, is absolutely nothing.” Wiggins then asks, “Were there many public spaces for lesbian women of color?” to which Shavers responds with laughter,

"Now I know that’s a joke, right? … I never grew up feeling I was entitled or had a right to have any space, or a right to exist. If when I was 15 or 16 they had put up barriers I would have just gone along with it because that’s how I was conditioned … it’s not like how it is now, we didn’t have no gay churches, no lesbian and gay center, no newspapers, no people fighting for lesbian and gay rights, we didn’t even have civil rights."

Joan Nestle, of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, is also interviewed, seconding Shavers’s point about potential violence against lesbian women:

“We lived with violence, but we lived.”

Like Ann Cvetkovich’s recent work on gay and lesbian archives, An Archive of Feelings, and Halberstam’s “Brandon Archive” (about Brandon Teena), such archiving marks an attempt to combat the obliterative homophobia and transphobia of official history, and the harmful effects of historical amnesia (made all the more urgent faced with AIDS and violence against transgender people). But documentary cinema is also clearly a means of anamnesis, a way of un-forgetting, “unlosing” (Halberstam 47), and archiving queer history, social tactics, and spatial practices (Payne).

We can also see hints of this in Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris Is Burning, during the 1989 epilogue when Willi Ninja (Mother of the House of Ninja) explains that people complain that the Harlem drag balls are not what they once were. He says,

“I really do miss the street element. I mean, but everything changes, and everything’s been changing drastically, you know—New York’s not even the same.”

Willi Ninja also makes an appearance in Fenced Out, and he and Malkia Cyril each explain the importance of voguing contests on the pier. In the video, Cyril makes a powerful argument that echoes the moral thrust of Delany’s above-quoted speech in The Polymath:

“All displacement is, is moving people from one part of the city to another part of the city, it’s not like they disappear. If they move from here the only place they’re moving to is the jail.”

Over shots of a crowd dispersing, a voice-over makes a similar point:

“Now they kick us off the pier at one o’clock and like they come along with little cars and like ‘Get off the pier’—and their whole issue is we’re on the streets, we’re on their streets and we’re lowering their property value because we’re in front of their building, and if they kick us off the pier, where we gonna go? On the street.”

As Delany insists, viewing these people as marginal “excess” is not acceptable in a democracy. Another major activist “veteran” in Fenced Out, Sylvia Rivera (of Street Transgender Activist Revolutionaries), remembers how

"all these piers were old piers and white middle-class men were having sex all hours of the day and night, this was their playground, Christopher Street was their playground. They had white male hustlers on Christopher Street. So for them to turn the tides around on the people of color and the trans community now in the year 2001, 32 years after the Stonewall, I find it completely unacceptable."

The “them” here implicitly refers to white middle-class (gay) men as the current agents of oppression in the name of property values. But while there is certainly some truth in this account (the negative side of enthusiasm for “gayborhoods”: see Nero, “Why Are the Gay Ghettos White?”), the experiences of Delany, Sankofa, and one African-American survivor in Gay Sex in the 70s contradict this sweeping characterization of the early Christopher Street pier as white and middle class.

Fenced Out performs important cultural work by desegregating and connecting queer generations, working against what Eve Sedgwick has identified as the

“systematic separation of children from queer adults; their systematic sequestration from the truth about the lives, culture, and sustaining relations of adults they know who may be queer” (2).

The emphasis on timely, youth-produced videos is obviously salutary (the typography and music instantly date the video, but this must mean that it appealed to its contemporaries). However, the division of the credits between “featured youth” and “featured adults” may unfortunately reinforce a youth/adult binary that is not terribly useful for queer lives. Halberstam, for one, is critical of social service outreach programs for queer youth that

“make a sharp division between youth and adult, and often set up the two groups as antagonists. I would also claim that the new emphasis on queer youth, can unwittingly contribute to an erasure of queer history” (176).

But clearly, Fenced Out is not guilty of such an erasure, in that it seeks to honor the past history of decades of queer activism. Like Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History,” the video manages to avoid the error of

“assigning the working-class the role of the savior of future generations [thereby severing] the sinews of its greatest power. Through this schooling the class forgot its hate as much as its spirit of sacrifice. For both nourish themselves on the picture of enslaved forebears, not on the ideal of the emancipated heirs” (Thesis XII).

Fenced Out and The Polymath attempt to represent a social space that is under siege by police who act in the interests of the ruling class. Clyde Taylor has described “New U.S. Black Cinema” in terms that are immensely helpful for thinking about this social space:

“Indigenous Afro-American films project onto a social space … It is a space carrying a commitment, in echoes and connotations, to the particular social experience of Afro-American people. It establishes only the slightest, if any, departure from the contiguous offscreen reality” (233).

Taylor offers Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama (1976) as an example of the struggle to make independent black cinema, including run-ins with the police in the Watts section of Los Angeles (like that between the New York police and the girl who initiated Fenced Out). Taylor argues that the

“social space of many new black films is saturated with contingency. Simply, it is the contingency of on-location shooting. But what a location. It is a space in which invasion is imminent. A street scene in these films is a place where anything can happen, any bizarre or brutal picaresque eventuality” (234).

While it is hardly neorealist, The Polymath nonetheless attempts to portray this contingent social space, and Delany emphasizes that this space carries with it a commitment. We can hear the urgency in Delany’s defense of queer inter-class interracial social institutions, even though The Polymath does not make use of the “direct address” style of Fenced Out, which has lines such as this:

“Do you chill at the pier? Do you like being able to come to the only queer youth hang out area in the city? Well guess what… the pier is already fenced off and soon the pier, as we know it, will be gone.”

Polysemy

Fenced Out uses Madonna’s nostalgic ballad “This Used To Be My Playground” (ironic given Sylvia Rivera’s accusation), but in The Polymath, Delany is not content to relegate his experience of the satisfying “sexual generosity of the city” to a nostalgic past realm. Delany insists,

“It is not nostalgia to ask … How did what was there inform the quality of life for the rest of the city? How will what is there now inform that quality of life?” (Times 147).

Unfortunately, this expression has been appropriated to act as a smokescreen for ruthless demolition and capitalist construction agendas. In Fenced Out Emanuel Xavier says,

“I think it was a lot more welcoming before the whole Giuliani era and the whole ‘quality of life.’”

Like the young gay men interviewed about their image of the “hedonistic” 1970s during the closing credits of Gay Sex in the 70s, the past confronts the present with this real question of “quality of life.” Documentary cinema can serve as a technology of cultural memory, bringing about this confrontational effect of challenging the present. My hope has been to place Taylor’s film within a larger set of documentaries and texts that make for “good company,” demonstrating its affinity less with the recent spate of biographical intellectual profiles, and more with the “engaged” depiction of queer of color social spaces.

|

|

| The Henry Hudson Parkway trucks seem like christened ships: “Allied,” “Liberty.” | Reason Clothing’s snarky “GO <3 YOUR OWN CITY” shirts. |

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 51

JC 51 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.