JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

Nicolas Saputra and Adinia Wirasti as Yusuf and Ambar, “generic” representatives of the lost generation that has come of age during Indonesia’s post-dictatorship Reformasi.

Tiga Hari’s views of the road fluctuate between the idiosyncratic local and an undifferentiated, postindustrial landscape that could be almost anywhere in the world.

Many of the standard tropes of youth on the road are deployed by Tiga Hari, only to be subsequently thrown into question as the film’s formal, stylistic, and narrative elements are put through a series of breaks and shifts, as if trying to shake off the film’s initially empty exuberance and examine the pervasive, underlying sense of stagnation that defines the characters’ life in the present.

The first narrative and stylistic break point of the film occurs during a drug-saturated party in the West Javanese city of Bandung, known for its independent music and fashion scenes.

Tiga Hari presents a transformed, but less hopeful take on Indonesia’s best and brightest in 2007. Yusuf attends a prestigious university in Indonesia, while early in the narrative Ambar discovers she’s been accepted to study abroad in England.

Dead bodies on the roadside in rural Java as seen from the protagonists’ car window.

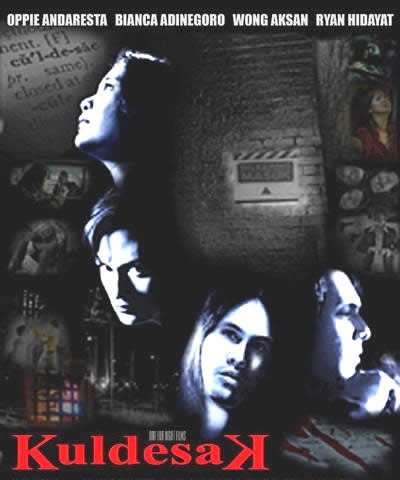

Poster for the collaborative film Kuldesak.

Ada Apa Dengan Cinta: If Dian Sastro can’t change the world, no one can.

Once on the road, Tiga Hari begins to blend the generic with the idiosyncratic, often presenting its protagonists at odd moments – there are several shots of Yusuf urinating outdoors, usually after taking a wrong turn or otherwise becoming lost or distracted.

Vehicles of various kinds, including the narrative variety, break down throughout the film.

Suf does his best to stay focused on the task at hand — transporting a suitcase full of precious dishes.

Ambar takes refuge from her troubles in an upscale dance club.

Sukarno the populist anti-imperialist at the height of his power. He remains a legendary figure in both Indonesian and global political memory.

Suharto, in the days before he was known as the “smiling general”: during his ascent to the presidency in 1965-67, he ordered the military to do away with 500,000 - 1,000,000 of his fellow Indonesians.

The famous monument at Lubang Buaya in Jakarta, commemorating the seven officers killed during the September 30th movement and demonizing the PKI for allegedly masterminding the operation. A life-size, blood-and-gore-filled wax figure exhibit and museum of the PKI’s “betrayal” of the nation were later constructed adjacent to the original monument. Even after the fall of Suharto in 1998, the site continued to win national accolades for “best tourist attraction.”

Now smiling in 1967, Suharto put a friendly face on authoritarianism and state repression for over 30 years.

Let’s get lost: unmapping history and Reformasi in the Indonesian film Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya

From the first frames of the opening sequence of the film Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya (Three Days to Forever, dir. Riri Riza 2007) there is an immediate sense of familiarity that hovers somewhere between nostalgia and déjà vu. This will arguably function quite differently depending on the audience, but as Indonesian viewers and critics have asserted, as have those in the West and elsewhere, the film, particularly early on, presents itself as a, fun, formally typical coming of age adventure. [1] [open endnotes in new window] In it, the two protagonists – a pair of upper-class, cosmopolitan hipster cousins in their late teens – embark on a classic road movie-style journey across the island of Java. The trip, of course, promises to take them, however briefly, out of the formal strictures of family life so that they can stretch, rebel, “find their own path,” and have a little fun on the way before returning to the sanctity of their planned and privileged lives. The film opens by introducing a classic “deadline” structure: Ambar, the female cousin, has missed a plane to her older sister’s wedding in the city of Yogyakarta, and Yusuf, the male, has been charged with rescuing the now-endangered unity of the family, and of the tradition-laden event: he must deliver Ambar, and an important and fragile set of ceremonial dishes that belong to the family, to Yogyakarta before the wedding commences.

Just as the protagonists’ journey is about to begin, however, the film takes a pause, the first of a number of such instances that both emphasize, and establish, a growing tension with the seemingly universal genre conventions that the film deploys. On their way out of Jakarta, the capital city, Yusuf, who is played by Indonesian teen-idol Nicolas Saputra, grabs what has thus far appeared to be a map rolled up on the back seat, ducking into a small bungalow. The interior of the space is filled with late-adolescent, coming-of-age-flick references and symbols: rows of pot plants, reggae-inspired colors (in this case they are applied to a sign advertising Aceh, the area of Sumatra typically known as the heart of Indonesian marijuana production), and a stoner send-up of a Disney/Pixar film poster. The title, “A Bug’s Life” has been switched with “a bak’s lah,” Jakarta slang for “let's get high,” a deceptively complex phrase that is echoed in various moments throughout the film. The bug’s eyes have of course been rendered as droopy and blood-shot. It is moments such as these that appear to justify the complaints of many Indonesian viewers in particular[2] that the film, despite its censor-challenging drug references, presents an über-typical combination of cinematic characters, narrative genre, and cultural references. Western critics looking for alternatives to the dominant, global influence of Hollywood may cringe as well at the specter of a long history of Disney-fied cultural imperialism hovering in the background.

|

|

| Pot for plans appears to be a mutually satisfactory exchange. A “tamed” representation of Hollywood’s continuing global invasions ... | ... hangs next to a poster claiming that Aceh, an area of Sumatra known throughout the history of the archipelago for its fierce resistance to outside intruders, is “for peace.” |

|

|

| The familiar antics of comedian Ringgo Agus Rahman are soon left by the wayside. | "Not in the mood for love": Tiga Hari often uses its roadway mise-en-scéne in humorous ways that subtly reinforce its struggles with the strictures of popular genres like teen romance. |

Yet it is precisely here that Tiga Hari’s complex self-positioning within a highly specific Indonesian, Javanese, aesthetic and political landscape begins to take shape. The altered Pixar poster, with all the banal familiarity it brings to the local, can also be read in terms of a literal coming of age for contemporary Indonesian films and their viewers: it brings to mind the prominent placement of the original A Bug's Life logo in the mise-en-sc~ene of an earlier, formulaic-yet-politically-driven teen romance film – Ada Apa Dengan Cinta (“What’s Up With Love” Soedjarwo 2002) – a smash hit that was crucial in re-establishing the popularity of Indonesian cinema with Hollywood-saturated local audiences. That film, produced by Riri Riza and also starring Nicolas Saputra and co-starring Adiniya Wirasti (who plays Ambar in Tiga Hari), focused on the entanglement of group of clean cut, wholesome-seeming upper class teens in the lingering sociopolitical problems associated with the regime of the recently deposed dictator, Suharto (1967-1998). After showing its critical teeth, however, the film ends on an ostensibly happy note, in which the spunky, talented younger generation it depicts seems poised to overcome the nation’s dark history (about which more later), that had just begun to enter into the teens’ burgeoning self-awareness.

|

|

| In the film Ada Apa Dengan Cinta, the bedroom of Cinta, the bright, popular and rich high school student played by Indonesian superstar Dian Sastrowardoyo, is dominated by references to Western popular culture. | In Ada Apa Dengan Cinta, a younger Nicolas Saputra faces the political problems of his family’s (and by extension the nation’s) past head on. |

|

|

| In Ada Apa Dengan Cinta, the repeated image of an empty, windswept schoolyard subtly conveys a sense of dread amidst the otherwise bright, carefree aura of upscale Jakarta in 2002. In 2002 this film was considered a coup against the strong national censorship board that seemed to bode well. | The sad, but romantic and hopeful ending of Ada Apa Dengan Cinta featured the first onscreen kiss in a modern Indonesian film rated for teenage audiences. However, current filmmakers continue to struggle with unpredictable and staunchly conservative censors. |

By placing two of the same iconic actors, now visibly older than fifteen, in roles with similar geographic (Jakarta) and class backgrounds, Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya effects a local sense of continuity that is potentially troubling in its response to the passing of time: it presents a second, post-high school coming of age in which things have changed, but not necessarily progressed as planned. The modified poster, then, and the altered lifestyles and mind-states of the protagonists in Tiga Hari on one level announce the erosion of a previously-heady sense of confidence in the young to become true agents of political and social development. The comfort emanating from the film’s warm, familiar imagery appears to rely on the lingering, subsidized stability of upper-class privilege associated with the long dictatorship of the recent past: the active, enthusiastic filmic youngsters of 2002 have now retreated into a decadent, “generic” stasis, reflected in Tiga Hari’s employment of a stoney, slowed-down version of an established formula combining star-power with ever-popular themes. Despite its celebratory, quasi-rebellious teen spirit, then, as Indonesian film analyst Ekky Imanjaya argues, Tiga Hari’s leisurely, rambling journey is haunted by the possibility of permanent stillness: the constant proximity of death (Imanjaya, multiply.com).

Seen in this light, the film’s pointed glances at the eternally common details of its mise-en-scène reveal them to be sparkling with the uncanny, as if attached to a series of heretofore unrecognized memories that reach out through the film’s deceptively flat, generic representations of the present. The protagonists’ first stop at the pot-infused bungalow also signals a potential point of departure on a “bad trip,” in which the comforting meanings attached to the known, inseparable from the current status quo, are destabilized and left behind. Thus, what had appeared to be a map (it turns out to be a map of sorts: a blueprint) is quickly handed off to “Edwina,” the bungalow’s sole occupant and Yusuf’s dealer and fellow architecture student, played by omnipresent comedian Ringgo Agus Rahman. A typical stoner side-kick in a Rolling Stones t-shirt who sits picking his nose in front of the TV, he exchanges Yusuf’s neatly laid out plans and structural drawings for a lid of weed, closing the deal with what appears to be a self-consciously stiff and clichéd series of high-fives.

The moment, which officially kicks off the film’s departure for the Road, also inaugurates what is arguably its most important theme: the surreptitious linking of the alteration of everyday consciousness, with or without the aid of drugs, and the rejection of historically dominant forms of navigation and knowing – whether in the form of a map, a series of genre-conventions, or state policies that enforce historical amnesia. As I will elaborate further below, it is at this level that I locate the film’s subversive approach to popular form, and coded, yet pointed, intervention into a long, detailed, and fraught history of local and national expression in the twentieth century.

To this end, I engage the mostly literal interpretations of Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya (road trip; teen romance; the transformative escapade of two, privileged, stoned, Javanese, Westernized, Muslim cousins who inevitably end up sleeping together) as a valid point of departure for a closer reading that excavates the symbolic and allegorical meanings which give the film its potential political force. My reading of the film will entail placing it at the intersection of a number of sociocultural, economic, and historical currents, many of them reaching far beyond the geographical limits of island or nation. My goal, however, will be to highlight the ways in which such currents are seen and interpreted from a perspective that is, at least in part, oriented by a positioning on the ground of the “local.” My selection of this film in particular is based on a long-term interest in the history and politics of Indonesia, and in the prominent, often violently dominant role played by various Java-based discourses in the attempt imbue the troublesome, impossibly varied archipelago with a unified sense of political and cultural identity. (Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya and a majority of other “Indonesian” films are set in Java, and, more often than not, in the capital city, Jakarta, where most are also produced). As both a filmmaker and critic, I am inspired by the ability of Riza and certain other local directors (and production teams) to engage with sensitive, delicate, and controversial themes in films that toe the line, in provocative ways, between populism and high art, commercial success and political activism. To begin with, however, in light of the little-known status of Indonesian film history among most audiences outside of Indonesia, I will provide some contextual background.

As a contemporary cinematic text, Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya is a product of the rapidly-expanding “Indonesian New Wave,” a movement which began roughly a decade ago with the release of the independent, collectively produced film Kuldesak (Achnas, Lesmana, Mantovani, Riza 1998) (Sen 2006). Fittingly, the New Wave was conceived amidst the decay of Indonesia’s 30-year dictatorship under President Suharto, whose authoritarian, Western-friendly regime was finally brought to a close by the Asian Financial Crisis, forcing him to step down amidst massive protests in 1998. The same year, the small group of young, wealthy, and idealistic film school graduates loosely based around the production of Kuldesak began turning out films that both sought to challenge the dominance of Hollywood imports at the local box office, and to inspire frank, populist discussion of the state of the nation after its much-heralded turn to more representative government. In the best cases, such as the afore-mentioned Ada Apa Dengan Cinta, the expanding New Wave has produced well-crafted, mainstream genre films that have won the attention of larger audiences while simultaneously offering glimpses into the darker legacies of the recent past. However, although they have exposed some of the ripples and depressions in the uneven veneer of democracy that has characterized Indonesia’s post-Suharto, “Reformasi,” era, the national feeling expressed in many of the films is one of cautious optimism: progress and real change seem just around the corner.

Released in 2007, Tiga Hari Untuk Selamanya can thus be seen as a product of the current moment in Indonesia, a time particularly haunted by the continuing illusiveness of promised change and by the unfinished task of examining – and exorcising – the complex demons of national history and their myriad, ongoing links to the broader sphere of geopolitics. In the national context (the film’s main audience base is a national one), in light of Java’s longstanding self-imposition as the political and cultural centerpiece of the Indonesian archipelago, Tiga Hari can certainly be seen as continuing some of the problematic aspects of its predecessors: it engages both local and global discourses from a critical, but nonetheless narrowly proscribed, hegemonic position that has traditionally been aligned with the Indonesian state and those whom its policies empower. However, I will argue that the film, both in its visual style and narrative development, simultaneously attempts to undermine and destabilize the broadly understandable, and profitable, sense of Javanese, Indonesian, or cosmopolitan/ transnational “normality” that has characterized cinema in the reformasi period. Driven by the protagonists’ boredom and the sense of near-meaninglessness of narrative attempts at forward movement or alteration of the status quo, the film has a vastly different feel than most of its New Wave predecessors, despite its obvious similarities with earlier works.

Drawing on popular modes of expression, like romance and travelogue, that echo their ubiquitous deployment in the present – and in more overtly state-glorifying ways during the Suharto past – Tiga Hari ultimately works to unravel the naturalized authority of such mainstream genres. While it begins, as explained above, by offering what seems to be just such a recognizable structure and star-studded story, as the dismissal of the formal blueprint/map in the early stoner scene suggests, it quickly strays from its well-trodden path. Through a series of subsequent stumbles, hesitations, and apparently chance encounters, it finally comes to a stop in the middle of its own narrative trajectory, alienating itself from the expectations associated with its initial, promissory deployment of form. Mimicking contemporary political and aesthetic stasis in order to challenge it, director Riri Riza (with screenwriter Sinar Ayu Massie) essentially place their protagonists in a worn-out, re-hashed and stalled genre pic that they must find their way out of. In so doing, they create the impression of a search for a deeper level of meaning or experience beneath the film’s own sketchily rendered slickness. The terms of the search are not stated, however, but revealed by the protagonists’ apparent blunders, as Yusuf and Ambar collide with the formal, sociopolitical, and physical limitations on theirs and others’ movement within the film’s diegetic world. Although they occupy a traditionally privileged, transcendent position, here, this is precisely what blocks their ability to engage with the fullness of experience that resides outside their highly constructed, typical upper-class Javanese “movie-lives” (and just beyond the glass, metal and rubber structure of their car).

Despite Tiga Hari’s visible struggles with the enabling, limiting status of class and form, however, it offers little in the way of either literal resolutions or larger, concrete allegorical solutions. Rather, it works slowly, on an intricate, piece by piece basis to construct something like a methodological approach, revealing the present historical moment to be full of shifting, gleaming shards of a “vanished” past, and suggesting places to look for those who might become inclined to start digging. The meaning located by such a method could, depending on the stakes of the viewer, be microscopically subjective and read-larger at the level of village, city, island, or, of course, “nation.”

As I hope to show, this approach implicitly takes aim at a number of the lingering structural paradigms put in place by the Suharto regime. In its reference to mobility and travel in particular, it engages the state’s longstanding use of an idealized “tourist” aesthetic to transform the nation into a well-ordered, easily readable, series of points – a populist narrative – that has been broadly figured (and enforced) as constitutive of a kind of default National Character. Re-entering this discourse, or rather showing that Indonesia continues to be immersed in it, Tiga Hari gradually chips away at the ubiquitous, reified conceptions of tradition and modernity in which it initially appears to traffic. In order to engage with Tiga Hari’s static, contemporary narrative space, which I argue is heavily freighted with the events and policies of Suharto’s prolonged dictatorship, it is thus necessary to include a brief but pointed exposition of the recent past. As a number of critics and historians have demonstrated [3], many of the failures of reformasi are intimately, if for the most part unspokenly, tied to the historical events of the latter half of the twentieth century.

1965 and the rise of the New Order

The heavy-handed tone of Suharto’s authoritarian rule was set from its very beginnings, in particular by a scene of terror and bloodshed that in many ways constituted a second, far more deadly “re-birth” of the newly independent nation. After a decade of political and economic uncertainty under Sukarno (Indonesia’s first president 1945-1967), during which the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) had rapidly expanded to become the third largest in the world, then-General Suharto, a staunch anti-communist, seized a chance opportunity to intervene: using the mass media, he accused the PKI of masterminding an attempted coup d'état that occurred on October first, 1965. (The accusation has since been shown to be a gross oversimplification: the action, ostensibly aimed at pre-empting an attack on Sukarno, was secretly planned by two members of the PKI in collaboration with a few Sukarnoist members of the military, unbeknownst to much of the PKI leadership) (Roosa 2006). While the oddly disorganized movement was quickly foiled and caused relatively little damage or instability, it did claim the lives of several Army Generals. Based on this news, a story was rapidly concocted and disseminated in which the Indonesian communists figured as bloodthirsty radicals bent on mass murder.

In “response” to this perceived threat and the apparent national state of emergency, Suharto claimed special powers for the military, effectively sidelining Sukarno. Wasting no time, Suharto quickly ordered a “pre-emptive” strike, sending the army on a wave of killing across Java, Bali, and Sumatra, wiping out the unarmed and unprepared PKI, from leadership to rank and file. Amidst the atmosphere of suspicion, chaos, and terror this created, villagers and officials alike were hurriedly rounded up as lists of “subversives” were compiled by local, military-friendly contacts. “Communist” quickly became a blanket-term, deployed to justify the rapid elimination of not only the PKI, but much of the pro-Sukarno or pro-left opposition. As Suharto’s power grew (he officially became president in 1967, but had for all intents and purposes been running the country since early 1966), many village officials, neighbors, and sometimes even family members suddenly turned informant or joined militias, re-mapping local conflicts onto the rather arbitrary, Cold War-inspired line now drawn across the nation: by accusing a former rival of association with the “left,” one might position oneself safely on the “right,” causing one’s enemies to literally disappear into the ground.[4]

The result of the actions of Suharto and the military was the so-called New Order regime, essentially founded on the murders, over the course of a few months, of 500,000-1,000,000 of its own citizens. Victims of the killings were most often thrown into mass graves or riverbeds, where their bodies would be washed out to sea. In this context, if not for the extreme measures immediately taken by the military/emerging state to control and suppress information — particularly any accounts of recent history that might hint at the actual numbers of dead, or suggest the military’s actions to have been anything but necessary and heroic — the New Order would likely have found itself unable to justify its own assumption of power.

|

|

| With support from president Sukarno and a massive ‘proletarian’ base, the Indonesian communist party (PKI) grew rapidly – and generally peacefully – from the mid 1950s... | ... until 1965 when it was decimated and banned by Suharto and the Army. Here, Sukarno is addressing a packed workers’ rally prior to 1965. |

|

|

| A suspected PKI prisoner “interrogated” in 1965. Houses, businesses and other spaces thought to be associated with the PKI ... | ...or the diverse, contemporary left-leaning organizations were often leveled during the months of heaviest violence. |

This left the government with a rather paradoxical problem of time. In order for the nation — the harmonious, unified and communist-free Indonesia envisioned by the New Order — to claim itself fully realized as such, the state would always have to return to its point of origin and obscure the violent nature of its break with the past, covering the steps it had taken to remove the purported communist “enemy within.” Thus, throughout Suharto’s reign, state narratives, national monuments and commemorations, and official histories continually revisited the events of 1965, hovering, dancing, or marching around the truth of the New Order’s ascent so as to ensure that it remained obscured by a veil of state rhetoric and otherwise off-limits to public discussion. This incessant zeroing out of national time, meant to remind citizens of their need for the state’s protection, was accompanied by official policies that effectively extended the originary myth of the threat of communism into eternity. As historian John Roosa argues, “the regime could not allow communism to die because it defined itself in dialectical relationship with it or, to put it more precisely, the simulacrum of it” (2006 13). Even now, over a decade after the fall of Suharto, large, official banners warning of the dangers of “latent communism” are a frequent sight in many cities.

In significant ways, then, the New Order government’s “prolific cultural terrorism” (Heryanto 1999 148) kept the nation in a state of temporal and ideological flux, always on high alert against the fabled return of a repressed“inner left” that could purportedly attack at any moment, re-immersing the country into the real chaos of the past. The state’s ongoing and ever-vigilant monitoring and control of the public was thus at some level always a veiled warning that if provoked, it could strike again with impunity and on a massive scale. The New Order’s manipulation of history, collective memory, and time, while never seamless or absolutely definitive of citizens’ experience, nonetheless constituted a massive, well-coordinated, and pervasive influence on behavior and experience. What Krishna Sen (1993, 1994, 2006) refers to as the state’s “turn inward” post-1965 in an important sense also constituted a turn to the media, attempting to police the “orderedness” of the nation as conceived through a series of representations. According to this plan, the ministries of information, culture and education offered citizens multiple exhibits of the past and of “themselves” — ideal, unrealizable models for history and citizenship, filmmaking and reporting, cultural identity and artistic practice — meant to be studied and mimicked, but never changed or exceeded.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 53

JC 53 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.