Politics and participation

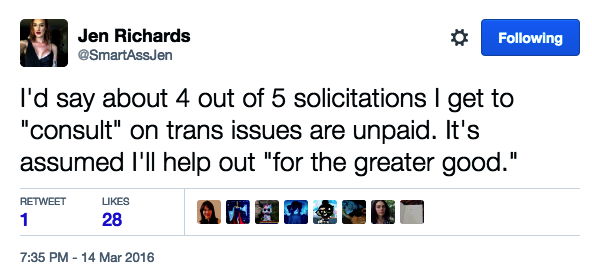

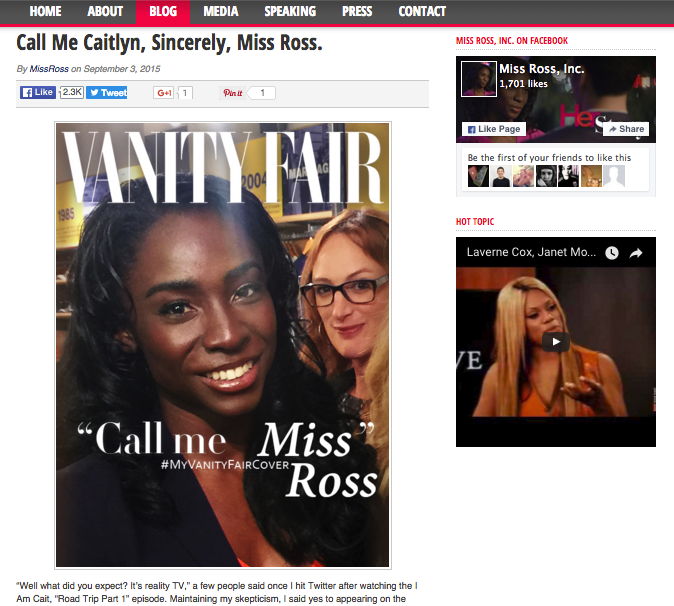

Between the filming of seasons 1 and 2, the political stakes for I Am Cait significantly rose. The backlash against Jenner’s wealth, privilege, and political views arose from many quarters, but particularly from among trans advocates and activists. This also included cast members from the show. For example, a withering blog post from entrepreneur and activist Angelica Ross detailed how her brief appearance had been misleadingly edited to silence her, diminish her accomplishments, and contribute to the show’s “white savior” narrative. [See image below.]

Specifically, Ross recalled Jenner’s initial assurance that I Am Cait ‘would be different, not just your ordinary reality show, but a docu-series,’ and accuses Jenner of ‘a gross misuse of power and privilege as an Executive Producer of her own show.’ In light of this, fellow activist, filmmaker and Ross’s close friend Jen Richards did not return to participate in season 2.

For cast members that continued between seasons, their participation did not signal begrudging acceptance of Jenner’s right-wing politics. In fact, many of them were vocal about their disbelief at her views, and the writer and academic Jenny Boylan even disclosed how she tried to leave on the second day of filming.[8] [open notes in new window] But instead of quitting, Boylan and performer Candis Cayne, artist Zachary Drucker, activist Chandi Moore, writer Kate Bornstein and new cast-member Ella Giselle maneuvered nuanced discussions of trans politics and subjectivity into the heart of the show. Against a backdrop of the 2016 election, the group countered Jenner’s dogged fiscal conservatism with a passionate argument for the value of identity politics, and they used the impact of legislation on transgender lives in order to make their case.[9] This complicates the power dynamic of I Am Cait between producer/star and supporting cast; that Boylan served as a consultant for the show troubles this even further. Her role, however, does not appear in the opening credits, and is only mentioned in a post on her personal website (Boylan 2015). As Nicole Morse argues in their article, identifying the precise nature of the labor performed by trans consultants is a difficult task, and Boylan only revealed the details of her consulting work in an email interview for this article. Having been shown the story arc of each season at its start and then a rough cut of individual episodes, she was able to make final edits before the show aired. She indicates that in the first season she ‘edited quite strongly’ as ‘it was important to me that we get all the language right.’ In the second season, though, ‘there was less of this—I was less concerned with walking on eggshells then, and thought it better that we get messy’ (Boylan 2016c).

Although Boylan’s editorial decisions controlled whether moments of conflict in I Am Cait made it to air, determining whether these discussions themselves were pre-meditated is ultimately a speculative process. Approaching the show through the discursive framework of social media, though, helps to illuminate the motivations behind the cast’s performances, and the political intent of the work they undertake. And as Web 2.0 fostered audience behaviors that ultimately shaped the production of I Am Cait, so too does it provide a lens for unpacking the work of its participants. Figuring such work as performative also draws the group into questions of what “trans media” might mean. For instance, if their intervention is a mode of performance, then what does it say about trans cultural production more broadly?

As Joshua Gamson notes in Freaks Talk Back: Tabloid Talk Shows and Sexual Nonconformity, sexual and gender minorities regularly appeared on TV screens throughout the 1980s and 90s, but had ‘no choice […] between manipulative spectacle and democratic forum’ (Gamson 1998, 19). Since the emergence of Web 2.0, though, trans subjects have gained agency as both political actors and cultural producers in the field of mainstream media. But if these new technologies have enabled a new form of queer performance, though, and this performance is indeed political, then what exactly are its politics? By looking beyond the cast of I Am Cait’s arguments about Presidential candidates and into their discussions of identity, race, and relationships we can find subtler forms of activism that challenge viewers to re-assess how they they relate to those around them. Although partisan politics guides the show’s narrative, it functions as a framing device for this more ambitious project. Here, trans-affirming pedagogy comes with a reconceiving of “community” and “difference” aimed squarely at a mainstream cisgender, heterosexual (cis-het) audience. Although I argue that I Am Cait is borne from cynical viewing cultures, its appeal to sincerity in fact marks a unique turn among docu-soaps that is central to its participants’ community-building efforts. By producing a Vérité-inspired “real” within the framework of Web 2.0, the show encourages its audience to respond directly to the cast’s public pedagogy online. In turn, the “authenticity” of these social media interactions—un-influenced by TV edits and delivered in real time—builds virtual community between cast members and viewers that subsequently affirms the sincerity of the show itself.

In Episode 2 of Season 2, a debate between Bornstein and Boylan exemplifies the cast’s efforts to shift I Am Cait’s focus away from its central star. While the group are riding from Los Angeles to Santa Fe, Jenner’s hair stylist asks Bornstein if the word “tranny” is used among trans women, or if it always offensive. When broadcast, the word was not bleeped, and cast members proceeded to discuss the complex relationship between pejorative slurs and marginalized social groups. Bornstein responds by explaining how the word was first used by the trans community in the 1970s, that she herself identifies as a “tranny,” and that those who find the term offensive are ‘very invested in being women, not trans folk.’ At this point Boylan interjects to point out that she is one of those trans women, and that she finds the word triggering since she previously experienced physical transphobic assaults. Bornstein tells Boylan that she’s not going to stop using the word, and asks Boylan to hear the ‘love and respect’ in her voice when she uses it; Boylan responds by telling Bornstein that Bornstein is ‘asking a lot,’ as it’s ‘not an easy thing for [her] to do’ (“Woman of the Year?” 2016).

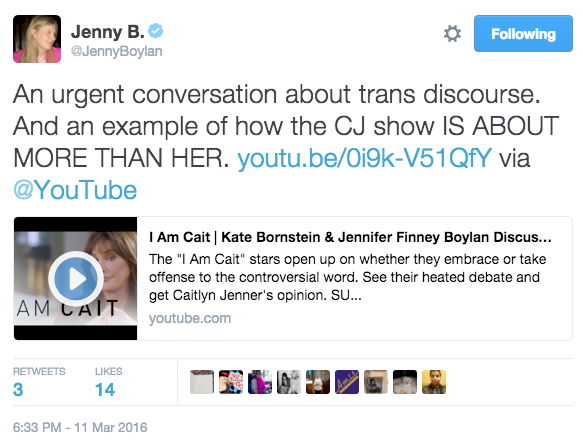

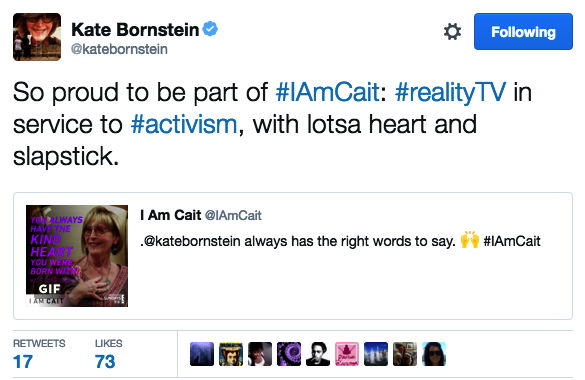

Throughout this scene, Jenner sits in the background and only gives a brief comment at the end. And although her distance from the action is self-evident, Bornstein and Boylan’s re-iterated their attempts to move the narrative of I Am Cait beyond the show’s namesake when the clip was shared through social media networks. After the footage was uploaded to YouTube, Boylan tweeted a link to her followers and explained how the scene was: ‘An urgent conversation about trans discourse. And an example of how the CJ show IS ABOUT MORE THAN HER’ (Boylan 2016a). As the season progressed, Boylan provided regular commentary and interacted with fans through Twitter. She explained that she disliked the filming process but was happy with the final result, and pointed viewers towards upcoming topics the group would address (such as trans women’s opinions of drag, employment discrimination, and the experience of trans women of color). Most significantly, she and Bornstein have used Twitter and media interviews to make their political intent for the show resolutely clear: Boylan repeatedly states that I Am Cait is ‘the most progressive, subversive, radical show on TV’ (Glock 2016), and Bornstein posted that she was ‘so proud to be part of #IAmCait: #realityTV in service to #activism, with lotsa heart and slapstick’ (Bornstein 2016). [See tweets below.]

|

|

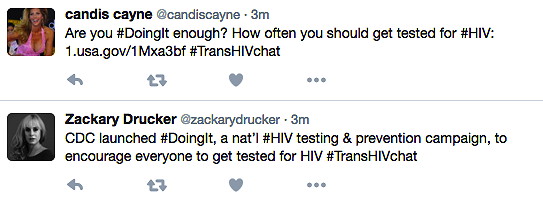

The pair’s social media posts indicate how Web 2.0 expands the discursive possibilities of docu-soap production. The show’s participants can now parlay brief performances on screen into more nuanced discussions online, and thus extend the life of a few short minutes of footage. While this often related specifically to events in the show, the cast of I Am Cait also used their new profile to engage in public discussions on trans-specific topics: on April 18th 2016, for example, the group held a Twitter conversation on HIV testing and treatment using the hashtag #TransHIVchat. The collectivity of this work echoed their performances during the show itself, in which visible moments of community and sisterhood were evident throughout. In particular, an encounter between the cast and Jenner during episode 2 revealed their collective resistance to the show’s star while also demonstrating the value of difference and diversity among their own small group. [See tweets below.]

|

|

Shortly after Bornstein and Boylan’s “t-word” debate, the whole cast confronted Jenner in a Santa Fe hotel about a particularly heated argument on the tour bus. They told her that they were threatened and intimidated by her aggressive behavior and felt unable to engage in conversation for fear of her response. During the ensuing exchange some cast members also revealed their behind-the-scenes discussions over whether to participate. Boylan and Bornstein had spoken with each other before agreeing to sign on for the season, and they now said that they had expressed reservations about appearing together, given their differing political views and the possibility of conflict that might arise. The two explained how they had ultimately agreed to participate in filming, though, and decided that I Am Cait’s overall positive effects would outweigh any such risks.

Their explanation of this process clearly models the form of inter-personal communication they later claimed as their objective for the show. As with their “t-word” debate, the pair showed how diverse viewpoints are shared even among broad political allies, and that community entails listening and accepting such difference. Indeed, in an ESPN interview they even assert that I Am Cait’s trans content is incidental to their broader political goals. Bornstein explains how:

‘That we are all trans makes the [political] debate easier for people to watch. It’s like, look! Trans, trans, trans! And the deeper stuff is taking place simultaneously.”

Boylan goes further, contextualizing their work against the backdrop of the 2016 election:

“In my opinion, the show is not about Caitlyn Jenner and it's not about trans people. The show is really about: How do we talk to each other? The country is now full of people who disagree. And no matter who wins the White House in November we are still going to have a country where about half the people don't talk to the other half. How do we have a conversation with people with whom we disagree, with respect and love?” (qtd in Glock 2016)

Although Boylan may claim that I Am Cait is ‘not about trans people’, I believe that the show contains a dual function. Its cast members performatively demonstrate ways of understanding and accommodating difference, yet this broad goal of transforming community is inextricable from the trans-affirming pedagogy that it provides. While the show’s majority cis-het viewers are taught how to communicate with love and respect to those that may be different, that very “other”—the trans subject—is visible, present, and speaking on their screen. Not only this, but the show’s participants stage debates and actions that loudly proclaim the validity of trans experience, culminating with repeated acts of civil disobedience in the season 2 finale, “Houston, We Have a Problem.”

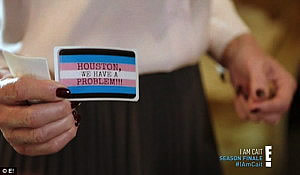

Following the repeal of the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance (HERO) by public vote in November 2015—after transphobic campaigns that argued the non-discrimination by-law would allow male paedophiles into women’s bathrooms—Jenner arranged for her cast to travel to Texas to speak with Mara Keisling, executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality, and pastors who had backed the repeal efforts. After being warned by Bornstein that they risked the possibility of arrest, the group drove around the city to use multiple public restrooms and left signposts reading ‘trans women used this bathroom with no problems.’ Their intervention marked a visible defiance of the Republican-sponsored “bathroom bills” across the United States that have attempted to restrict public restroom access according to gender assigned at birth, yet also pointed to the broader challenges of navigating public space as a gender non-conforming subject. The mediation of group’s protest in Web 2.0 contexts also reflects how technology has been used by queer and trans communities to orient themselves through the gender-regulated public sphere (e.g. the open source web application Refuge Restrooms, which combines mapping software with a user-generated database to direct users to the nearest gender-neutral or gender-inclusive restroom in their area).

I Am Cait’s trans participants, then, are visible, vocal, and political actors, yet they also speak and perform to complicate the notion of what or who a trans subject is. Throughout their many group discussions, cast members publicly challenge normative assumptions about trans subjectivity. In particular, they work to deconstruct a singular, unifying model of trans womanhood. Not only is Jenner’s role as the supposed face and voice of the trans community quickly dismantled, but so too is any notion of a fixed trans experience that binds the rest of the cast. Thus, while Borstein sees “tranny” as a ‘family word,’ Boylan finds it offensive, and while Cayne and Moore express a love of drag, Boylan finds it problematic. In this way, cis viewers are reminded that trans identity is articulated on each individual’s own terms, and that being an ally to the trans community entails stepping back and learning to listen.

As an extension of this work on trans subjectivity, then, the show’s cast—the majority of whom are independent cultural producers—also challenge the notion of trans cultural production as a coherent genre or set of cultural practices. I Am Cait is a performative media production by and about trans people, but to label it a work of “trans media” perhaps misses the point. Indeed, the show is generative precisely because it unpacks the very notion of singularity or unity on which a coherent genre relies.