4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days

at the moment of

neoliberal catastrophe

“… the guilty should pay” — Gabita

Endless neocolonial wars, genocides, immigration crises, sovereign debt, global warming and racism at the state level are signs in the present global crisis of what Walter Benjamin would have called “catastrophe” and what Naomi Klein calls “disaster capitalism.” A critical response to this crisis calls for a transnational perspective—one that engages the global crisis at a national context and treats national themes and crises as variations of the global crisis. As a medium of global communication, cinema operates simultaneously on global and local national levels, and as such, cinema is the perfect transnational locus for critical intervention. By entering the global market with a universally appreciated thematic as its “cultural commodity,” small national film productions, like those from Romania, invite a global critical response, which in turn, by interpreting the creative ambiguities of the film’s images in different cultural contexts, may clash with, or rupture, the local national interpretative frames of the film’s analysis. Such clashes of interpretation may open up the national cinema to a transnational critical perspective.

As a case study of a critical site of the transnational clash of global versus national interpretative frameworks, I will offer an analysis of the 2007 Romanian Palme d’Or winner by Cristian Mungiu, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, not as it is more commonly interpreted as a commentary on the Romanian Communist past, but rather as a critical allegory of the Romanian neoliberal future.

The film tells a fictionalized version of a true story dealing with an illegal abortion during the Communist prohibition on abortion. It traces that experience as undergone by a young Romanian student Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) and shows the rape that she and her friend Otilia (Anamaria Marinca) experience by the abortionist Mr. Bebe (Vlad Ivanov) in exchange for his service. The ghost of Communism underpins previous interpretations of Mingui’s film. In this case, interpretations converge around the claim that the film is about the two women’s experience of the regime’s structural misogyny. That seems to be the critics’ sole entry into the Communist past.[1] [open notes in new window] As Constantin Parvulescu in his 2009 Jump Cut article puts it, the film “… is ultimately the story of two friends and a friendship”[2]; for Doru Pop, Mungiu’s film “is a moral questioning of how people can make bad decisions and act maliciously against their fellow human beings”[3]; Dominique Nasta situates this “moral questioning” within “the ‘war between women and Ceausescu,’” adding that the film can be seen“ as a kind of slice of life, a critical fragment of the existence of these two girls under Communism, showing how true friendship and solidarity were at work.”[4] Notwithstanding the obvious relevance of such analysis, in my view, these analyses leave out an important untapped pool of signification in the film. In short, Mungiu has cooked for us more than the critics have served.

Instead of purchasing a critical entry into the Communist past from the standpoint of “oppressed subjects,” I will offer an analysis of the villain. By deploying the strategy of dialectical reversal, I will view the abortionist from the Communist past as an allegorical inscription of the Romanian neoliberal future. As a cultural criminologist, I surely appreciate the dialectical reversal of U.S. villains into social critics. Such is the mafia mob Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), the main character of the HBO TV series The Sopranos (1999-2007), who, as an allegory of the social critic, puts a criminal face on U.S. global power.

In fact, Tony Soprano’s crimes of racketeering pale in comparison to the white-collar crimes by his Wall Street golf-club members who were plotting the financial catastrophe of 2008. Here one can recall Bertold Brecht’s line from The Threepenny Opera (1928): “What is robbing a bank compared to founding a bank?” Furthermore, Soprano’s homicides and torture pale in comparison to the crimes against humanity and torture committed by George Bush’s government while the show was aired. The fact that mafia mobs all eventually face justice while politicians and bankers do not reveals that criminals remain within the boundaries of legal justice as most of us do, while politicians and bankers are above it. This unjust discrepancy gives the villains the status of critics of the system.

To some extent, the villain in Mungiu’s film, Mr. Bebe, is at once a victimizer in the Romanian past and a critic of the Romanian neoliberal future.

At first glance, the story about abortion and rape in Communist Romania has no tangible link to present-day global capitalism, but abortion and rape do speak to a global audience. Analyzing the previous film interpretations of rape and abortion as metaphors of Communist oppression from an U.S. neoliberal context allows for a transnational co-extension of this metaphoric meaning to U.S. “disaster capitalism,” with let’s say, rape as its metaphor, or, in other words, it allows us to read the Romanian past as a neoliberal present. To this end, I argue that Mungiu’s film in the character of Bebe, perhaps unconsciously, stumbles upon the Romanian neoliberal future in this film about illegal abortion from the Romanian Communist past.

To be fair, Mungiu himself in one of his interviews stated that his “dark and sober film” “inspects the side effects of Communism … from a very human perspective.”[5] But in another of his interviews, he frames the Romanian economy as the film’s preamble about illegal abortion:

“It was a way of saying that we have to boost the economy: to complete our plans in economics and agriculture we therefore have to increase the population. … Because of this reasoning, abortion was forbidden for much of the population.”[6]

Mungiu’s ambiguous intention allows multiple and unexpected interpretations. Surely, one can interpret Gabita’s and Otilia’s rapes as a manifestation of their “tacit resistance”[7] to the masculine cruelty of the regime and see Otilia as the Romanian version of Sonya Mermeladova from Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, who prostitutes to feed her family. But if we step outside the implicit humanism of the victim, we are left with the reality of the disciplinary and dehumanizing power of global capitalism. Considering the historic fact that neoliberal capitalism invented the International Monetary Fund (IMF) during the Cold War precisely for the purpose of economically destabilizing countries like Romania to use national debt to intensify internal tensions and lead to social rapture, then “the side effects of Communism” extend to neoliberalism as well.

Surely, Gabita and Otilia were dehumanized by abortion and rape. However, as the film shows, they made a choice to these ends so that their dehumanization belongs not to choice-less Communist power but rather, as we will see, to a liberal power. And that power deploys choice and contract to transform Gabita’s and Otilia’s subjectivity to submission. More likely, as I will address further, Gabita’s and Otilia’s dehumanization resembles that of Maria (Luminata Gheorghiu) a Romanian woman from Michael Haneke’s film Code Unknown (2000), who endures dehumanization on a Paris street corner as a beggar.

Mungiu’s film 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, is part of his series of films about life under Communism called Tales From the Golden Age. The film is the most recognized and awarded film in the basket of the Romanian New Wave cinema, which emerged on the global scene at the beginning of this century. Films such as 12:08 East of Bucharest (2006) The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (2005), The Paper Will Be Blue (2006) Aurora (2010) Beyond the Hills (2012) harvested numerous awards at prominent film festivals in Cannes, Berlin, Chicago and Locarno and earned the praise of film critics around the world.

As a whole, these films make up perhaps one of the most significant small national cinemas with the creative power of small and cooperative productions challenging Hollywood’s expensive and studio production industry. These are low budget films, with a common minimalistic aesthetic of social realism, all telling dark stories, shot with a fixed camera in real time and filled with rigorous dialogue. The directors, cinematographers, and script writers also like to call themselves the “generation of the decree,” referring to the Government’s antiabortion decree 770/66 introduced in 1966—more about this later. Born in 1968, Mungiu regards his film as an autobiographical return to the time when the government had forced his entire generation of future filmmakers into life. Naturally then, dialogue with the ghosts of the Communist past directly or indirectly dominates in all these films.

The plot

Mungiu’s film 4 Months… tells a story based on a real event about an illicit abortion paid in the form of a “voluntary” rape at the time of Ceausescu’s antiabortion regime. The central character in the film is Otilia, a young woman who takes on the burden of helping her college roommate Gabita get an illegal abortion. The story begins with two female students in their dorm room getting ready to meet an abortionist recommended by a friend. Gabita is the pregnant one and is somewhat disorganized in contrast to Otilia, who has taken it upon herself to organize the entire illegal operation. They go over the list of things needing to be done: Otilia is to meet her boyfriend to borrow additional money for the abortion and to check in at the hotel recommended by the abortionist. And while Gabita waits in the hotel room, Otilia is to meet the abortionist at the agreed time and place. In addition, we learn at her meeting with her boyfriend that Otilia is expected the same afternoon to attend her boyfriend’s mother’s birthday party.

For the time being, Gabita disappears from the story and the camera follows Otilia running around to collect money from her boyfriend, pay for the hotel room and meet the abortionist. Unexpected glitches follow her in the process. First, the hotel reservations made by Gabita earlier over the phone turn out to have not been confirmed, and additional free rooms are not available due to a convention in the city. She thus goes to another hotel and checks in. But because a single room is not available, she has to check into two rooms, which cost more than planned. She then meets the abortionist, who arrives by car at the designated place just as Otilia arrives. They meet, and another glitch emerges: to his surprise, the one who needs the abortion does not show up as agreed. His dissatisfaction and suspicion grow after he learns that they did not secure a room in one of the two hotels he had asked for. After getting assurances from Otilia that he can trust them, they head to the hotel where he meets Gabita.

|

|

| Solitude in action. Otilia leaves the dorm on the way to the hotel where Gabita will have an abortion. Her mundane appearance conceals her illegal project. | Double bedroom, an ominous sign of a double rape. |

He immediately expresses his dissatisfaction about Gabita’s failure to follow their agreement and sets up a commanding tone in order to prevent any further glitches. With a stern voice, he outlines the criminal and medical consequences if things don’t go his way. He explains the procedures: “After I put the probe in, you’ll bleed and the fetus will come out.” Gabita must remain still until the fetus comes out, which can last two hours or “three-four days.” He further instructs her not to let anybody into the room, and in the case of serious complications she should call medical emergency and hope for the best. All in all, after the procedure is done, she is on her own. During the course of his examination of Gabita it turns out that she is further along in her pregnancy than she had told him and Otilia, which only further complicates her abortion and adds to Bebe’s suspicions about her. He nonetheless agrees to proceed with the abortion under the condition that he is not paid in money. This puzzles the women and during the course of heated exchanges, it becomes evident that in return for his service he expects to have sex with both of them.

We learn that Gabita had agreed during her phone conversation with Bebe that instead of monetary payment they would “work something out.” He insists that their agreement should be honored. They protest, he threatens to leave, and Gabita and Otilia accept his demand. The rape scenes are left out. Gabita waits for her turn outside, smoking in angst; then Otilia waits for Gabita in the bathroom. This takes place in the room where the procedure is performed, and then instructions are given to Otilia to throw the wrapped fetus “down the rubbish chute.” After Bebe leaves, the two women sit in silence. After a short reflection about the event, Otilia heads to the birthday party while Gabita remains alone in the room.

At the party, Otilia maintains her composure, torn between her rape experience and insults by the guests, middleclass academics, about her modest social upbringing—she is the daughter of a soldier—while her boyfriend remains a silent bystander. Otilia leaves the party unhappy about his passive attitude and heads to hotel room. There she encounters a somewhat confused Gabita in the bed and the fetus on the bathroom floor. As instructed, she takes the fetus wrapped up in towel. She heads out into the night with the promise to Gabita that she will bury the fetus; in the course of finding the place she ends up throwing the fetus into a trash container. Upon her return to the hotel, she encounters an empty hotel room, only to find Gabita at the dinner table in the hotel’s restaurant waiting hungry for her meal. To her question “Did you bury it?” Otilia reminds her of their agreement and asks her never to talk about it again.

|

|

| Otilia finds Gabita in the bed motionless; she wakes up confused as if waking up from a nightmare. | The fetus wrapped in a white cloth laying on the cold marble floor teases out the Biblical image of baby Jesus as if he were massacred by the hostile world. The shot of the fetus conveys powerful anti-abortion sentiments. |

|

|

| Otilia throws up after disposing the fetus in a trash container as if her body were rejecting her new subjectivity. | Gabita worries for a proper burial of the fetus. In the background is the wedding party’s music that amplifies her moral ambiguity, which was so harshly disciplined by Bebe. |

Bebe’s disciplinary power

As Foucault pointed out, power is the relation of forces, of one action against another, creating a relation of domination and submission. As Kristin M. Jones correctly observed, “Bebe is a law outside the law,”[8] meaning that his power comes not from Ceausescu’s law as the law of the country but from some other register of power—it comes from his language. As we will see from the conversation in the hotel room, Bebe’s language primarily functions not as an instrument of communication, but rather as a disciplinary instrument of submission. Bebe’s illocutionary power arises from his perverse use of a “speech act,” of Gabita’s agreement with him “to work something out,” as an institution of contractual obligation.

There are two structural preconditions at work in Bebe’s rape narrative. The first is his understanding of woman as the agency of distrust, and the second is his masculine language of terror. Both preconditions appropriate a power grid based on creditor-debtor relations. Bebe’s rape narrative can be broken down into three strategic segments: contract, debt, and payment.

Contract:

If Gabita and Otilia’s submission to rape marked the total capture of feminine chaos, the sloppy preparations for Gabita’s abortion mark the beginning of it. As agreed, Bebe arrives on time by car to pick up Gabita, but Otilia shows up instead. Gabita, he learns, is waiting not at the hotel as he had demanded. Sensing potential danger in this disorderly beginning, Bebe stops the car. “Trust is vital.” Otilia offers an assurance, “You can trust us completely.” Bebe takes her answer as confirmation of what in his mind is an oral “contract” between Gabita and himself.

Debt:

As a creditor, Bebe understands that the economy of debt is predicated on guilt. As soon as he meets Gabita, he capitalizes on her sloppiness and instantly establishes a strategic dominance to increase the volume of Gabita’s guilt. “We’ve got off to a bad start, young lady.” His long silence gives gravitas to his words and forces Gabita to own the guilt. He has no time for small talk. Instead, he handles the conversation as a war of positions. His stern, patronizing voice broken by significant silences draws a line in the sand from where he gives orders to establish control over what he has perceived to be a dangerous feminine chaos. As if speaking to a child, he repeats his instructions. “I told you two things on the phone. One, get a room at the Unirea or the Moldova. Two, meet me in person. You think I asked for the sake of it?” By not following his instructions, Gabita has created a dangerous situation, which opens an abyss of guilt from which she and Otilia will crawl out raped.

From the start, Bebe sets up disciplinary parameters and reduces Gabita’s and Otilia’s maneuvering space to avoid rape. After the physical examination, it becomes apparent to him and to Otilia that Gabita is beyond the fourth month. This dishonesty only increases Gabita’s overall debt-guilt to Bebe. “I don’t know, miss.” Bebe responds, “It is very dangerous. Who did you think you’d find to do it [short silence] in the fourth, fifth, whatever month it is?” What he means to say is “because your condition is far more medically and legally dangerous, your debt to me will increase.” Bebe bargains as if at a bazaar, “But everything in this world has its price.” “We’ll pay!” Gabita insists, but to her horror she will soon learn that she is also a debtor in a new kind of economy of debt.

Payment:

Establishing the inventory of Gabita’s broken promises and positioning himself as the victim, Bebe moves in to close the deal. First, to Gabita’s mention of payment, Bebe looks at her with mild surprise, “Young lady, did I mention money? Did I mention money on the phone?” Otilia intervenes with an explanation. Ramona, the friend who recommended him told Gabita the price for his services would be 3,000 lei. To nip the situation in the bud, the girls hope for a monetary exchange. Bebe, turns the conversation to Gabita and to his previous agreement.

|

|

| Bebe’s disciplinary interrogation reveals Gabita’s evasiveness about her late pregnancy; his terrorizing brings truth into the open and uses it to further subject Gabita to his perverse desire. | Otilia explains to Bebe that they are short on cash only to realize that money was never to be the means of transaction. |

|

|

| Bebe reminds Gabita of their agreement “to work something out” instead of being paid. Bebe uses this agreement as a strategic advantage over Gabita’s desire. | Otilia’s ‘cognitive dissonance’ marks a rupture in the situational frame of reference. |

Before inflicting a shock, Bebe strategically offers a narrative of a ‘mutual aid’ as a rationale for their submission to him. “Young lady, what did I tell you on the phone?... That I understand the situation, and I could help you. Right? Did I mention money?” In response, Gabita reiterates Bebe’s words, “You said we’d work something out.” With Gabita’s confirmation about their agreement, Bebe passes halfway through the very sensitive part of “negotiation.”’ “Precisely. That is why I asked you to come in person. So that we could work something out.” Gabita should appreciate, he continues, that he does not judge her, since, “In life we all make mistakes.” He has not, he further reminds her, probed into her personal life, “I asked you nothing, not your name, nor the father’s name. It’s not my business.” On the other hand, he had nothing to hide. He came with his card and he left his ID at the reception desk. “If the police come, they’ll get me first. I am risking my freedom.” This would be damaging for him given that he has a family and a child.

“So if I’m nice to you, if I help you, you should be nice to me too, right? That is how I see it.”

“Wait… I’m not sure I understand.”

Otilia senses trouble. To avoid a reversal of the shock therapy so carefully handled, Bebe reminds Gabita about the asymmetry of their strategic relation: he can wait but Gabita cannot, “You are the one in a hurry.” It is too late for any misunderstanding. He leaves no space for the girls’ conversational comeback or for a U-turn in their negotiations. He presses on with his victimization,

“What did you think? I risk ten years for 3,000 lei? Is that what you thought? What do you take me for? A beggar? Did you see me begging? Here’s what we’ll do.”

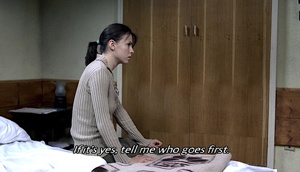

At this point the camera shifts from Bebe to Gabita sitting on the edge of the bed fearfully awaiting what is about to hit her. We hear Bebe’s voice:

“I’ll go the bathroom. When I come out, you will give your answer. If it’s yes, tell me who goes first. If it’s no, I’ll get up and go. It was you who came to me for help.”

The clarity is finally delivered without mentioning the “it.” The part “tell me who goes first” clarifies everything. We see Gabita’s face in horror as she utters, “I feel sick, I can’t believe this is happening.”

Heated negations follow as Gabita and Otilia raise the price to 5,000 lei, promising money they don’t have. Bebe rejects it; angrily, he heads to the door. Blocking Bebe’s exit, Gabita finally capitulates: “Please help me fix it… the way you said.” “The way I said?” “Yes, the guilty should pay. I screwed up.” She is suggesting “My friend is under no obligation.” In a stern voice, Bebe utters, “You don’t suggest! If anything, you ask. I said I’d help and explained my terms. If you don’t understand, no one’s forcing you.” To end this painful exchange, Otilia shouts in a crying voice, “Fine! Give her the probe and …” Bebe asked, “And what? You think I was born yesterday?” Otilia sits on the bed and takes off her shoes. To their horror, the “it” is about to happen. As if in the marketplace, Gabita and Otilia have made their choices and they have closed the transaction.

|

|

| Gabita experiences a radical shift of situational meaning. The time of catastrophe begins. Everything up to this point reads as a dream about two naïve women believing that money could buy them an escape from an unwanted pregnancy. | Captured by her own desire, Gabita capitulates and accepts the ‘terms’ of the agreement she made with Bebe on non-monetary payment. |

|

|

| "The guilty should pay." Gabita’s induced guilt is the only bargain. She has to stop Bebe from leaving. | Otilia is ready to “go first” … |

“Mr. Bebe”: allegory of a neoliberal catastrophe

Although Romanian and Western film critics place interpretative gravitas on Otilia and Gabita’s moral predicament, in my view they have failed to appreciate fully the interpretative value of Bebe’s language. For example, Ioana Uricaru characterizes Bebe’s language only as “verbal abuse”[9]; for Doru Pop, Bebe’s language is “the cruelest sequence of the movie”[10]; and Dominique Nasta characterizes Bebe’s dialogue as “probably the most explicit and crude of the whole film.”[11] Western film critics tow the same line. Kristin M. Jones characterizes Bebe “in a frighteningly modulated performance”[12]; Damon Smith registers Bebe as, “increasingly hostile over their inability to pay his asking price”[13]; Ann Hornaday sums up his character as, “alternately practical and monstrous”[14]; while for Stephanie Bunbury he is “the strange, mysterious Bebe.”[15]

To be sure, all these enlisted putative features signify the power of Bebe’s cruel masculinity, but they say nothing about its technology. As authorized by Mungiu’s illocutionary genius, Bebe is comparable only to David Lynch’s perverse illocutionary monster articulated by Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) from Blue Velvet (1986) in his erotico-terrorizing scream, “Don’t you fucking look at me!” Perhaps Parvulescu unknowingly inscribes a nightmarish Frank Booth into Bebe when he observes that “Once Otilia and Gabita leave the dorm, their privacy is stripped from them. The abortionist enacts a nightmarish embodiment of such exposure”[16]—much like, one may add, the one experienced by Dorothy Valence (Isabella Rossellini), who is stripped of her privacy when exposed to the nightmarish Frank Booth in her own apartment. Bebe’s type of person would be well known to any Romanian, like Frank Booth, who, according to Lynch, is “a guy Americans know very well.”[17] In this vein, Parvulescu describes Bebe as “the ultimate other of real existing communism’s atomized society, unmasking its proximity to a contractless Hobbesian state of nature.”[18] Similarly yet somewhat differently, Frank Booth, as I would paraphrase, is “the ultimate other of real existing capitalism’s atomized society, unmasking its proximity to a contractual Hobbesian legal state.”

The liberal words “trust” and “free choice” dominate Bebe’s language and allow Gabita and Otilia to come to his submission of their own volition, which Nietzsche locates in the meaning of the German word Schuld (which means both “guilt” and “debt”). Although the oral contract between Gabita and Bebe rests on his “barbaric” side of power, Bebe’s strategy nonetheless operates within a “liberal situation,” like one in the market economy. Gabita has a “choice” not to submit herself to rape by not having an abortion to the same extent that a worker has a “choice” not to work (until he/she signs the contract). What forces Gabita and Otilia to be raped is precisely the forced guilt of the contractual relations so dramatically expressed by Gabita’s “the guilty should pay.” So, by inserting Ceausescu’s “absent presence” as a mediating force regulating Otilia and Gabita’s silent submission to Bebe’s sexual violence, in much the same way “that the social violence of the regime was accepted by women and men alike throughout society,”[19] Pop contradicts his own claim that Ceausescu’s power did not stem from the perversity of the social contract, but Bebe’s did.