III

“I don`t know anybody who has been as happy I`ve been. And when I start describing “happiness”, the amplitude and prolonged periods of happiness that I’ve known, especially in my teens – people don’t believe that. I was so happy that it made me dizzy… …There are recurrent themes in my films and one of them being certainly the idea of youth. Well, I just realized that. I told you before I had such a happy youth, maybe I’m still longing for it…. by making the films, I’m trying to go back to that period or to that – not so much that period – but to that way of being; the way it was to be young, which I enjoyed so much. And so those themes come back.… the loss of youth. And Mon oncle Antoine and Wow and Dreamspeaker is very much about that…. There are obvious things [that inspire me]. Like sexual things, my libido, and it drives me and if you can call that inspiration.… [C]ertainly my libido drives me to put things in films and there are things there that are quite clear to me and some not… , [sexuality]'s one of the most enjoyable things in life and if I have one regret in my life, well it is and it's not, is that I didn't enjoy it more when I was in my prime and when I should have been sexually, when I physiologically more active. But , I'm mak ing up for that, I think, now. Now that all the guilt has gone. [I]t seems that I appreciate it that much because I knew what it was to be deprived from it because I knew how it was when it was forbidden and I knew what it was when every little satisfaction was counter-balanced by unbearable guilt, and all that. And, there again, [now] it comes too easy.…it's much too good for the kids. They don't know what they have in their hands; no pun intended.”

— Claude Jutra, 1979.[14] [open endnotes in new window]

A year after the 2016 scandal and Jutra’s second disappearance, a special Jutra section of another Quebec film magazine Séquences appeared: the tide had turned slightly.

Jutra’s name may well have disappeared from film awards in both Toronto and Montreal, and from Quebec topography, but in fact a more measured conversation has ensued and his films are more available than ever (not an easy challenge for feature films of the 1960s and 70s).[15] Interestingly the word “lynching” continues to turn up, in both the section and independently online, for example in the voices of the film historian Heinz Weinmann and inveterate feminist playwright Denise Boucher (Weinmann; Cloutier).[16] The 2017 authors however did not address the scandal in detail, as if it was time to move on, rather revisited certain Jutra films in a not very interesting way. However, they made sure alongside Jutra’s online defenders to disavow complicity with pedophilia of course. Of course. For the rest of this article I would like to think about my “of course.”

My point is not to question the veracity of the testimonies of the two survivor individuals who came forward in the initial media brouhaha.[17] I take them at face value in the spirit of the times and what I hope is our steady collective political growth around sexual violence since the 1970s. Rather, I would like to revisit certain of Jutra’s actual films that can be read as linked to the disappearance in order to illuminate them in the light of the fast-moving conversation.

As I observed in my book in great detail without ever having recourse to criminalizing labels, the pedophile sensibility is perceivable in almost all his films, in major ways in four works made in the key mid-career decade of the sexual revolution, ironically all produced for the state studios the NFB and the CBC respectively, and in two independent films I call the book-end films, produced at the very start and very end of his career.

First a breakdown of these six films in chronological order:

i) Le Dément du lac Jean-Jeunes (The Madman of Lake Jean-Jeunes, 1948). Jutra the teenager made this astonishing 40-minute fiction with his new birthday Bolex, his beloved scout troop, and his lifelong cameraman collaborator Michel Brault (two years his senior). Neglected by critics and largely unavailable, presumably as “immature” juvenilia, Madman offers a gorgeously photographed and accomplished narrative of a scout troop camping in the woods. The opening credits declare the film to be a campfire melodrama for scouts and it certainly is that, a child abuse melodrama. The scouts discover an isolated cabin where a strange drunken hermit figure is holed up in an abusive relationship with his son. Then the film's first person narrator, a 12 or 13-year-old scout, leads the troop’s rescue of the boy from the father who eventually falls to his death from a cliff, pursued by the troop who have become a vigilante mob of astonishing violence.

The film is also a lyrical black-and-white essay on the summer forest and on teenage male bonding and socialization, punctuated by not one but three collective bathing sequences, deliriously long and sensual, the Lord of the Flies going Boys in the Sand…. If we cannot call such a sophisticated amateur film naïve, we can perhaps use the word “uninhibited,” for the beefcake – or should I say calfcake? – is blatant with the scouts rushing into the forest streams for ritual baptismal communion at the blow of a whistle, even in the midst of orphan rescue (the narrator/protagonist performs his own striptease for the camera early on, throwing each garment in turn from off camera into the frame).

The abusive family (the abuse is physical violence, not spelled out as sexual) is a demonic opposite of this idealized scout troop, that same-sex parental substitute and institution of male socialization, but the narrator's voice-over reference to the passive son-victim muddies the neatness of the opposition: "He must be his son, he seemed to love him even if he was brutal." At the end, their mission of normalization completed, the scouts abandon their now domesticated orphan at a foster home of stultifying tranquility.

ii) Rouli-roulant (The Devil’s Toy, 1966). This documentary short about teen skateboarders in Montreal is a wry and self-reflexive nonfiction essay on the phenomenon, especially the adolescent protagonists facing the cops who are reinforcing municipal regulations banning the devices from sidewalks and roads (but who are on their best behavior in front of the cameras). Despite the a brief self-parodic demonstration of the construction and uses of the object that was just then being popularized beyond the boundaries of California, there is very little exposition in this gorgeously lyrical, even balletic, poem to homosocial agility and grace (several girlfriends and female skateboarders are in the picture without undermining the overwhelmingly male-gendered character of this world) – accompanied by a catchy song crooned by Jutra’s friend Geneviève Bujold (12 years his junior, soon to be the star of his most ambitious film, the historical epic Kamouraska, 1973).

|

|

| Poster and two frame grabs from Rouli-roulant. | |

The film’s epigraph, borrowed at the start of this article, literally applied to the processions of athletic, handsome, entitled youths floating through the streets and parklands of the wealthy enclave of Westmount, might also be an echo of the youth culture and impending “summer of love” that Jutra had certainly encountered in a recent teaching stint at UCLA (where he taught Jim Morrison!), and might of course stretch far beyond such narrow “between-the-lines” readings to embrace a more autobiographical register.

iii) Wow (1969). In this hybrid feature Jutra facilitated Québécois teens to direct dramatized cinematic narratives of their own fantasies about their lives and the world, interspersed with grave black-and-white interviews with the subjects about the world, sex and drugs and authority. Jutra’s most focused work on the 1960s youth rebellion, Wow has its predictable share of beefcake of course – even its public flaunting. The poster notwithstanding, male subjects outnumber female subjects six to three (and also predictably in this [upper?] middle-class universe, no class or ethnic diversity enters the picture). Wow diverges from its predominantly ephebocentric focus in only one climactic episode where pot-smoking Pierre fondly remembers his childhood encounter with a pet porcupine. The reminiscence is dramatized in sensuous black and white with the camera caressing an underwear-clad boy, perhaps five or six, as he caresses the animal on a gleaming hardwood floor.

Wow, poster and production still.

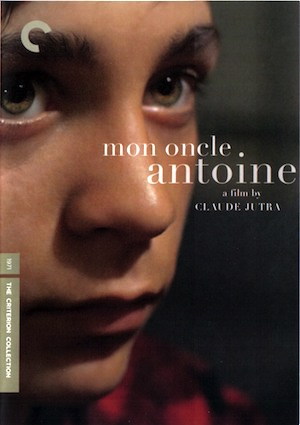

iv) Mon Oncle Antoine (1971) is the best known and most loved of Jutra`s work. This stature is due in part to its circulation in both languages, well managed by the NFB for almost a half century, in contrast to the erratic handling of the independent features À tout prendre and Kamouraska. Accessibility ensured in no small way that it would remain firmly entrenched for decades as number one on all-time Canadian ten best lists. This period feature follows a male teen coming of age in rural industrial Quebec within an extended non-consanguineal family that runs the local general store/undertaker salon. Silent, voyeuristic Benoît awakens to mortality and adult perfidy, but most importantly to sexual desire, feelings, and relations, whose complexity suddenly brings tears to his playmate Carmen`s eyes.

|

|

|

|

v) Dreamspeaker (1975) is the least known of Jutra’s major works, especially in Quebec, partly because it is in English, but mostly because this 75-minute made-for-television feature has been unavailable in either language for decades. Another melodrama, this Vancouver Island yarn follows Peter, an emotionally disturbed and orphaned blond pubescent boy who escapes his juvenile “facility” to spend a northwoods idyll with an indigenous elder-storyteller and his twenty-something adopted “son,” a friendly, mute woodcarver-muscleman. This mentor pair is an idealized alternative all-male family who feed and clothe the boy, pump up his self-worth, teach him therapeutic native lore and take him skinnydipping. Of course it can’t last, the trio are denounced by an urban handicraft dealer and the Mounties burst in to puncture their rhapsody. While the justice system may well recognize the men as Peter’s “natural parent” equivalents for visiting privileges in the “facility,” the elder dies of a broken heart after the boy is taken away and the other two younger ones follow him violently by their own hands.

White settler writer Cam Hubert, also known as Anne Cameron, responsible for the Dreamspeaker script and novelization, was married to the magnificent indigenous actor Jacques Hubert who played the mute woodcarver. If we needed to diagnose the lamentable current unfamiliarity of this work, one would have to attribute it less to its now-evident risqué undercurrents, than to the willful negligence of its institutional rights-owner the CBC (it has been totally unavailable since the NFB dropped it from its 16mm catalogue over three decades ago at least) and perhaps even to the slight embarrassment that could be sparked by its settler-authored indigenous narrative (which however needs no defense in its original context in my opinion[18]).

|

|

| Dreamspeaker: novelization cover and two frame grabs from skinny dipping/picnic episode. | |

vi) La Dame en couleurs (The Lady of Colors), 1984. Jutra’s last film is a period melodrama set in the same vague dark past of Quebec history – before revolutions both quiet and sexual – as Mon oncle Antoine. Another troop, this time not scouts but boy and girl orphans sequestered in an asylum run by nuns, seek freedom in the tunnels beneath the fortress-like institution. There they bond with an adult inmate, a kind of resident artist, a “dabbler” who has filled the underground with Chagall-esque murals – a part Jutra had written for himself but which the producers refused to allow him to perform for lack of star-power and growing evidence of his illness. The children are even more precocious sexually than Benoît and Carmen, and their ringleader, 15-year-old Agnès, even tries to seduce her own special nun-mentor by reading to her from The Song of Solomon! All eventually escape except for Agnès.

When I say that these six films are Jutra the pedophile’s most “explicit,” I mean that textual analysis for all six readily isolates idealizing, eroticizing, empathizing constructions of their frankly beautiful heroes (pubescent male heroes, that is, or post-pubescent in the case of Wow, and both male and female in all the films except those two taking place in homosocial woodland worlds, Madman and Dreamspeaker). Jutra explores the kids’ corporeal and moral agency and autonomy, their struggles against a harsh, violent and oppressive world as they mature, their engagements with learning and sharing within surrogate families and complex non-familial adult-child relations – in the context of tragic, rich, beautiful, complex, enduring and yes ambiguous narratives of nurturing and betrayal, abuse and revolt, resilience and mortality.

Bathing and other corporeal rituals are plentiful. The skinny-dipping sequence in Dreamspeaker in which the hero Peter, slightly younger than Benoît, frolics with his twenty-something mute muscleman mentor, endlessly splashing and leaping in the idyllic sylvan pool, urged on by both characters’ elder mentor onshore, astonishes the post-1980 viewer. Its bold, lush and unstinting frankness would not be allowed over the last generations: its sacramental role leads to it being reprised at the end of the film as a postmortem flashback (all three characters die with gruesome explicitness), anticipating other melodramas climaxing in “Lazarus endings” where the dead come back to life and party with the living, from Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) to Longtime Companion (1989) to Paris is Burning (1990) to Les Misérables (2012). One might make similar reflections on the fascination in all six Jutra pedophile films with same-sex play, combat and pursuit, the rituals of suffering and awakening of the growing and learning child.

Clearly all these films’ scopophilic fantasies privilege male subject/objects, most blatantly for example the graceful, agile skateboarders. I say subject-objects because the characters inevitably return the gaze, caught up in voyeuristic engagement with the adult world, the filmmaker in intense and complacent identification with their look. Benoît, altarboy and general store and funeral parlor errand-boy, whose shortness and prettiness makes him more boylike than his recently changed voice might imply and allow him to get away with more transgressions than most, not only plays sexual games with his peer Carmen, another castoff from the nuclear family who is an inmate of the establishment, but also spies on all of the adults in his world, the adulterers, the drunks, the blasphemers, the local bourgeoisie, both anglophone (the capitalist bosses, racist and patronizing) and francophone (the wife of the notary, treated like royalty by the storekeepers because she indulgently buys the most expensive corset in the catalogue and tries it on on the other side of the keyhole from lecherous Benoît). As the sexual revolution made its impact increasingly, and the walls of censorship crumbled, the films became increasingly astonishingly frank about childhood and adolescent erotic agency, and sexuality in general.

Adult mentorship had been a benign, even positive trope in Jutra`s earlier documentaries about education like Jeunesse musicale (1956) and Comment savoir (1966), aligning the idealist openness of children and teenagers with the beneficient nurturing of adults. The trope would be increasingly problematized as the director matured.The Age of Aquarius and the sexual revolution increasingly ushered in the utter incompetence or blind destructiveness of adult authority, for example the cops who clamp down on the idealized Westmount skateboarders in Devil’s Toy, or the range of authority figures excoriated in Wow, legal, religious, law enforcement, educational, parental and so on. Benoît is stuck with a drunken and incapacitated guardian uncle and a frivolous other adult male role model Fernand (played interestingly by Jutra, and constructed as a perfidious adulterer and creepy voyeur in a process of unfiltered brash confessionality). Male adult mentorship in Dreamspeaker is loving, wise, and supportive but also futile, so much so that the set at the end of the film is littered with almost as many bodies as Hamlet, the boy hero and his adult non-consanguineal kin succumbing bloodily to the scriptwriter’s nowhere-else-to-go.

Jutra’s kids always thrive, as least for a time, in their heterotopic world, whether sylvan or urban or underground, with multiple variations of mentorial or familial mentorship both good and failed/oppressive, and with tropes of rescue and failed rescue: Dreamspeaker shows by far the bleakest failure, but La Dame en couleurs with its doomed heroine Agnès is close behind (her nun mentor has escaped to the secular world, but the once vibrant teenager is sentenced to lifetime incarceration in the asylum).

In this broader view of the documentaries and features as complementary visions of these same processes of growth, education, and socialization, one thing is incontrovertible: Jutra's sense of these processes, the most profound within two Canadian national cinemas in which youth films have long been a privileged genre, is channeled and deepened through the physicality of his pubescent heroes and through his eroticization of their pedagogic interactivity – and through Jutra’s way of inevitably annulling and shattering the idealizations he has so lovingly crafted.

Jutra’s bookend films, Le dément du lac Jean-Jeunes and La Dame en couleurs, situated at the very start and the very end of his filmography thirty-five years apart, both melodramas about kids and their elders, deal with touching directness in not-so-coincidental symmetry and felicitousness with pubescent sociality and desire and juvenile sexual agency. I am sure that the impressionable young Jutra like everyone else had seen the most successful play in 20th century Quebec theatre, La Petite Aurore enfant martyre. This over-the-top pop melodrama told the famous story a motherless girl tortured to death by her evil stepmother, which never left the boards in Quebec between 1921 and 1951 and was soon adapted into the biggest feature film hit (1952) of the pre-Quiet Revolution grande noirceur (Great Darkness) period. Did the evil stepmother transmutate, on some unconscious level, into the vicious yet tragic abusive hermit father in Madman?

In his interviews Jutra almost always remembered an intense and blissful childhood (see epigraph). Surely this affect of nostalgia and loss explains the rich complexity of his portraits of kids coming of age, his erotic apperception of their growing bodies deepened by an intense identification with them. Perhaps this complexity explains how the erotic dimension of Jutra’s portraits and narratives could be disavowed by generations of critics.

Disavowal and avoidance also characterize the literature on Jutra to this day – even in the wake of the scandal, as we have seen. Both the English and the French literature, for all their instrumentalism in quietly maintaining the heritage, are selective in touching on the themes that interest me in this article, continuing to avoid what is on the screen. The only monograph in English, Jim Leach’s Claude Jutra Filmmaker (1999), is so subsumed by the Quebec national problematic of this Montreal filmmaker who made as many as eight English-language films in English Canada and was far from the most vocal spokesperson for the indépendantiste cause, is so perfunctory in treating the oeuvre’s queerness, that its readers must have felt especially blindsided by the eruption 17 years later.

IV

In conclusion, I would like to think about canon, archive and empire, or the political responsibility of the queer film historian – in 2017. The last queer film critic to use the word “responsibility” in a title of an article was Robin Wood in 1977, and this is the 40th anniversary (Wood, 1977). Robin’s argument is grounded mostly in this article in an auteurist tweaking of the canon, and Renoir, Hawks, and Bergman are all seen through brave, rose-colored glasses. My undeniable focus on the auteur – the oeuvre and the scandal who were Jutra – may seem to build on Wood`s heritage. Like Wood, I am prodded by textual pleasures, challenges and dilemmas, and ponder the ethical and political responsibility of the queer film historian – in 2006 and in 2017 – in the maintenance of the living [film] archive, in the modulation or defense or subversion of the queer [or national] canon.

But let’s get to the point, let’s go further: it is my responsibility to pierce what Jon Davies has called the “black hole into which any measured speech about consent, pleasure, and desire in intergenerational relationships seem to vanish” (Davies 2007) and I have done my best through the above largely textual operations. Even more importantly it is my responsibility – and all of our responsibilities – to situate these textual operations within a vision of a larger project of societal "liberation," as with Wood, and to call for, to engage in, to insist on, a far-ranging cultural and political conversation about intergenerational love, refusing the black hole. This conversation will engage with the meanings of sex, sex work and the criminalization thereof, sexual assault, sexual harassment, consent and age of consent, the sexual child, juvenile sexual agency, the queer child, sexual mentorship and pedagogy, sex education, the regulation, suppression and punishment of dissident sexuality in our culture, witch hunts and sex panics, the prison industrial complex and the carceral state, the war on sex offenders, and along the way the genocidal[19] campaign against pedophiles and boylover culture.

In short, the time has come to tell the truth, to take off the gloves, to shine light into the culture`s black holes, to lose the delicacy and nuance and irrelevance of academic insider address… and defiantly use the word “pedophilia” – not as symptom or forensic evidence – but as artistic dynamic intrinsic to Jutra’s and many others’ work, as intrinsic to our battle to maintain Jutra’s canonical status within Canadian, Quebec, queer and postwar international new wave/art/documentary cinemas. The time has come to do so – not in spite of (as in Griffith’s white supremacism or Heidegger’s anti-semitism or Polanski’s and Nate Parker’s sexual assault conviction or non-conviction) – but, as with Plato/Socrates, Abu Nuwas, Lewis Carroll, J.M. Barrie, André Gide, Benjamin Britten, Hakim Bey, and Michael Jackson, etc., etc., … because of.