JUMP

CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

At the screening of Harry Potter in the student center at Southern Illinois University, May 2002...

...children bring their Harry Potter paraphernalia...

...Film launches become “events” designed to sell not only a movie, but toys, clothes, videos, record albums, computer games.

Each of the film’s artifacts is up for sale, including its costumes such as the sorting hat and the magic cape, which cover these bed sheets made for children. Here the motif is the magic cape...

... and here the motif is the sorting hat. Film productions now depend on easy recognizability that can be translated across a wide range of commodities. This process places bounds on the utopian imagination in children’s culture.

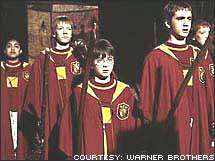

One of the ways the Potter enterprise “muggles” steal fantasy is by glamorizing class. Only the elite can attend Hogwarts expensive boarding school. The teachers dress in capes and gown, are addressed as Professor, and sit at High Table.

Even children’s uniforms are glamorized, as seen here in the school garb for aspiring witches and wizards.

In the space made for girls in this fantasy, Hermione fits the stereotype of the smart girl who is an annoyance.

Free

market, branded imagination —

Harry Potter and the commercialization of

children’s culture

I don’t know how the Muggles manage without magic.

... Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone[1]

Just when it seemed that magic had become passé even in its last home, i.e., children’s culture, along came J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. (Chris Columbus, 2001).[2]After all, children’s mass culture in the late twentieth century had derived a great deal of merriment ridiculing the idea of magic as the old fashioned ingredient of nineteenth century children’s tales. They were now simply too tame and, should we say, childish, for a generation that had cut its teeth on video games and marketing campaigns designed to address them as a niche market.

Now mainstream films made for general consumption, like Toy Story (1995) mocked the idea that stories of toys coming to life had to be imbued with mystery. When the toys came to life in this film they asked: “Are you from Mattel?” “Were you made in Hong Kong?” Or there are toothpaste commercials that deconstruct the tooth fairy by casting a man in drag as the tooth fairy. In a commercial for Disney Land and a Visa credit card, the child cajoles its parents to use the credit card, putting on an “innocent” face so as to win a trip to Disney Land, which had earlier cast itself as a magical place.

In contrast, Harry Potter, an orphan who is left to the mercy of his upwardly mobile, suburban aunt, uncle and cousin finds out one day that he is a wizard. He also finds out that there is an entire world, a way of life with its own language and culture that lives by magic. This world coexists parallel to the world of the “muggles,” the wizards’ term for the “normal,” routine bound, monotonous, magic less, everyday world. Did Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone then indicate a return of the utopian imagination in children’s literature and film? Not quite. Instead, Harry Potter is an excellent lesson about the limits of fantasy. Here that fantasy is produced as a commodity, driven by an industry that continuously raises the stakes for a film’s survival in terms of expected returns.

The film’s aesthetics make obvious the limits of the utopian imagination. The way the film was scripted and how it looks stem from the “mugglish” political economic realities of the film business at the end of the twentieth century. Ultimately we must ask a question as old as capitalism itself: What is the nature of magic that the market serves to its consumers? The cornerstone of free market ideology, as espoused by Hollywood, rests on a notion that consumer demand and not production relations determine product. In other words, it is not the producers who shape the film but those who consume it. What kind of magic wand could create such a vision? To unravel this riddle, we need to trace the historical trajectory of the selling of Harry Potter, that is, the transformation it underwent from a book that was not written as a film-to-be into a franchise, a pretext for selling other market-produced commodities.

In a rave review in Variety, Todd McCarthy reiterates the magic mantra that makes us responsible for the films we get:

For tens of millions of fans the world over who have taken J.K. Rowling’s marvelously imaginative novel (and its three sequels thus far) to their hearts, Warner Bros. smartly produced and elaborately manufactured $125 million-plus visualization will essentially make their dreams come true...[3]

Children’s film as a genre has led the commercializing of culture. It plays a central role in the construction of “consumption webs,” such that media, including film, and other commodities constantly advertise each other. Film launches become “events” designed to sell not only a movie, but toys, clothes, videos, record albums, computer games. A film’s release attracts so much attention that one would have to live in another world to escape it. A glance at the most successful high-concept or event films in the last decade shows the overwhelming importance of the children’s or family film in this category: Home Alone and Ghost (1990), Aladdin (1992), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1993), The Lion King (1994), and Titanic (1997).

As Justin Wyatt has argued, since the high-concept film is a marketing concept, it is designed to maximize returns by eliminating ambiguity. Productions depend on easy recognizability that can be translated across a wide range of commodities. They get recognizability through dependence on stars or genre and by having scripts based on simple narratives with stock situations and simplification of character and plot.[5] Janet Wasko has characterized this phenomenon as “cultural synergy.” Accordingly, in the preproduction stage, a film is conceived of as a brand. That is, companies promote their activities across a growing number of outlets. The activities and products related to a film can then be cross-promoted and distributed through media conglomerates across a range of media.[6]

Clearly this process places bounds on the utopian imagination in children’s culture. Thus, exploring the production and marketing of Harry Potter will aid us in understanding how the role of the consumer is drastically confined within this cultural environment. In terms of film, this cultural environment in which films are scripted and promoted is dominated by centralized media ownership and the convergence of media culture and other forms of commodity culture.