JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

-----

Black Journal:-----

-----

Richard Pryor -----

While the family on The Cosby Show must nostalgically recall the sixties and the civil rights

movement to address racism, their immediate television forebears did not have to look as hard to

find examples of racism to respond to, whether directly or indirectly.

Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson on Sanford and Son -----

Sanford and Son -----

Sanford and Son -----

The Flip Wilson Show -----

The Flip Wilson Show ------

The Flip Wilson Show ------

Good Times -----

Good Times -----

Good Times -----

Don Cornelius and Soul Train! in the 1970s -----

"This ain’t no junk"

Recuperating black television in the “post civil rights” era

Christine Acham. Revolution Televised: Prime Time and the Struggle for Black Power. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Revolution Televised: Prime Time and the Struggle for Black Power offers readers an accessible analysis of African American representations in the 1970s. In doing so, this volume critically updates scholarship on U. S. television’s representational economy. Research on African Americans and television is a surprisingly understudied area of television studies, yet it is crucial both to television history and to African American studies. The “Black Power” or “post civil rights era” saw increased black visibility on the networks, public television, and local television. However, many African Americans, who had criticized television for its exclusion of blacks, were also critical of these new representations. In attempting to contextualize these new representations, and the critical discourse around them, Acham challenges classic but overextended texts on African American televisual representation, such as J. Fred Macdonald’s Blacks and White TV and Donald Bogle’s Prime Time Blues. A review of these texts exposes the limitations of stereotype analysis, which tends to lump representation into the categories of “positive” and “negative” without looking for more complex interpretations or allowing for the possibilities of resistant reading. Acham goes beyond stereotype analysis to examine the class-based notion of “racial uplift” that informed the critical discourse around this wave of new programming.

Unlike earlier works on black television, this book considers television from a perspective that allows for considerable black agency. Acham opens up a dialogue around shows that have been all but forgotten, such as NET’s Black Journal, an advocacy-oriented documentary series, and the Richard Pryor Show, a short-lived experiment in which allowed Pryor, a comic artist known for searing critiques of U.S. apartheid and white hypocrisy, to have his own program on NBC. Not surprisingly, that program ended after four episodes. Acham also examines programs that some African American audiences considered to be “selling out,” such as Julia, a program whose protagonist, a nurse and Vietnam war-widow, seems to live in a racism-free universe, and The Flip Wilson Show, which, despite having writers such as Richard Pryor, was not as biting in its criticism of racism as some would have hoped. Acham recuperates and reassesses black family comedies such as Sanford and Son and Good Times, which have been maligned by critics as offering a negative view of blackness and black life. She attributes this negative assessment to middle-class bias wrapped in a notion of racial uplift.

By focusing on the class dynamics that influence whether critics view a text as “positive,” or “negative,” Acham situates her work as a critique of the politics of respectability that some cultural critics have employed in an unexamined way. This middle-class bias obscures “the history of black popular culture in which residual resistance exists in what may seem on the surface to be antiprogerssive texts.” (Acham 2) Moving beyond the categories of positive and negative, Acham asks, according to whom are certain television texts negative? This is an important question, as this conflict has been deep and lasting. For example, while the NAACP protested Amos’ n’ Andy, the program had many black viewers, many of whom did not appreciate the idea of someone else telling them what was appropriate for them to watch.

Acham grounds the history of seventies television in a black performance tradition that reaches as far back as the slavery period, tracing developments such as call and response technique and modes of mimicry and humor through the black theaters which eventually became the “Chitlin’ circuit.” This lineage is demonstrable but the analysis here could have been extended. The Black comedic traditions that circulated on the “Chitlin’ circuit” were demonstrably related to the black television comedies of the seventies. Radio and the race records industry also provided an outlet for these artists. While this history is not the focus of this work, a brief history of this relation would have been illustrative.

However the class divide in taste cultures that Acham traces back to this performance tradition is certainly relevant to the critical discourse around television. For example, these performances were avoided and criticized by middle class African Americans but appreciated and supported by working class African Americans. Building on Mel Watkins groundbreaking work on black humor, Acham argues that African Americans created humor and satire in their own communities that was unrecognizable by others.[1] The evolution of the black road show, with its roots in minstrelsy and vaudeville provided the first outlet for Black musicians and comedians such as Sammie Davis Jr,. Dewey “Pigmeat” Markham, Moms Mabely and Ethel Waters.

Moreover, Acham is able to draw stylistic and textual linkages between this history and black television in the seventies. This lineage is more than theoretical, as some of the performers on black television in the sixties and seventies were shaped by their involvement in these black performance spaces. Redd Foxx, a comedian whose Los Angeles comedy club was a venue for comedians ranging from the more mainstream Bill Colby to the controversial Richard Pryor, was also no stranger to controversial and “blue” material. While he apparently did not have a large white following, NBC saw the lucrative potential in brining him on board to star in Sanford and Son, a comedy starring an African American family based on a British sitcom. Redd Foxx played a widowed patriarch and his son Lamant was played by Demond Wilson. The two lived on a meager income in Watts, Los Angeles, made famous by the black uprisings there in 1965. While many criticized the show for its “negative” stereotypes about blackness, Acham points out that Foxx was able to use the venue to offer a showcase to a number of lesser known black artists who would make appearances on the show. Additionally, she points out that the white character was far more caricatured than the black characters and therefore, his portrayal represented a form of social critique.

Acham argues that the types of humor seen on television in the 1970s have their origins in “communal black spaces,” which were produced by the color line and Jim Crow segregation. Acham sees the emergence of these performance traditions from these spaces to the publicity of television as an emergence into the public sphere. She argues that this transition from African Americans laughing amongst themselves to sharing humor with a multi-racial television audience challenged white racism, celebrated working class black aesthetics, and made middle class blacks very uncomfortable.

While the forms of Black humor originating on the black theater circuit signaled resistance to white norms and white oppression, these forms were not designed with a white audience in mind. Thus, Acham argues, when comedies with their roots in this theater tradition began to circulate on television, a middle class concern with racial uplift informed critics’ dismissal of African American comedies such as Sanford and Son.

While her historical interpretation is based in secondary sources, Acham’s original contributions are evident in her close reading of the programs. Her class-based argument allows for new readings of texts that have been maligned and dismissed. Despite the tremendous structural racism in the television industry, Acham sees a possibility for resistance, and is able to demonstrate it convincingly. Significantly, she also focuses mostly on comedies, and situates enjoyment by black viewers as, itself, a possible form of resistance. She sees this enjoyment as politicizing rather than palliative.

“I highlight the many ways in which black people used the media, specifically television, for community purposes, as a political voice for social change, for enjoyment and for self affirmation” (Acham 20).

In the move from the near invisibility of African Americans on television in the forties, fifties and sixties to what Acham terms the “hyper blackness” of the late sixties and 1970s something important happened. Where some middle class critics see “jokesters,” Acham finds the possibility of resistance. Building on cultural history such as the work of Kevin Gaines, Acham ties the notion of uplift to middle class African Americans. She claims that middle class ideologies dominate the critical dialogue around black televisual representations in the seventies and lead towards dismissal. This is a mistake, as television was doing important political work during this revolutionary period in black history.

The later chapters, on Good Times, Soul Train!, Julia, Flip Wilson, Sanford and Son and the Richard Pryor show are particularly strong while the discussion of news and documentary are limited to a single news documentary on the Watts riots and a single episode of Black Journal. The later chapters assess programs as they changed over time, a key technique for television scholarship and a highly relevant one in these cases.

Thus, a significant contribution of this volume consists of in providing the history of understudied programs such as Soul Train and The Flip Wilson Show. Acham demonstrates why Soul Train has held up over the years while Flip Wilson has not. Flip Wilson’s show was a comedy/variety act. Wilson, who grew up desperately poor, joined the service at 16 and began a comedy career in the 1950s. By the 1965 he had appeared on the tonight show and had a considerable following. His work eschewed overt social critique of racism, which may explain why his show survived four years, while the far more overtly critical Richard Pryor was allowed only four episodes. While Acham argues that Flip Wilson’s more integrationist or mild stance made him more palatable to whites, she does not label him a “sellout.” Instead she points out that this “palatability” enabled him to bring a broad range of African American characters into U.S. living rooms. Pryor, of course, was not able to do this. In fact, he was somewhat demoralized personally by his experience of television’s hegemonic control.

In her discussion of Flip Wilson, Acham cites responses to certain Wilson personae such as the oft-repeated Geraldine Jones, originator of such famous phrases as, “What you see is what you get.” Despite Jones' popularity, Ache writes that some critics saw her as analogous to Sapphire in Amos n’ Andy (and therefore negative) (p 76.) Acham reclaims Geraldine: “Geraldine was strong, sharp, stylish, and had a cutting wit and a sense of self assurance.” However Wilson’s portrayal of working-class African American archetypes was distasteful to many middle class African Americans. Acham does an excellent job of demonstrating how Wilson was at once a symbol of African American success while simultaneously reminding viewers of vaudeville and even minstrelsy.

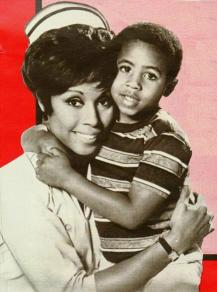

In addition to resistant performances, actors also exerted their influence by creating public discourse outside of their roles by giving critical interviews in magazines. Dianne Carroll did this, by speaking out against racism in magazines and making it clear that the rosy view that her character, Julia held about race relations was not one she shared. Good Times’s Esther Rolle, went several steps farther. First, anxious to avoid stereotypes, she refused to be part of CBS’s Good Times unless a black father was provided for the family that was the subject of the sitcom. Secondly, she spoke out very critically and was sometimes able to obtain script changes when she found objections to certain plots. And finally, she left the show for a time when the character of her son “JJ” played by Jimmie Walker, got too out of hand. She only returned to the show after concessions were made, but by then it was too late to save the show form its poor ratings.

Acham’s extensive description and analysis of the very short-lived Richard Pryor Show rounds out the text. She then concludes with an analysis of Chris Rock’s television work, which she clearly sees as inheriting the legacy of the black performance tradition addressed throughout the book. This conclusion and the arguments throughout the book are an important addition to work such as Herman Gray’s Watching Race, which celebrates the possibilities of the Cosby Show, but does not extensively address how social class affects spectatorship. Indeed, read against the Cosby Show’s blithe ignorance of day-to-day racism, the poverty and daily struggles portrayed on programs such as Good Times and Sanford and Son read far more strongly. While the family on The Cosby Show must nostalgically recall the sixties and the civil rights movement to address racism, their immediate television forebears did not have to look as hard to find examples of racism to respond to, whether directly or indirectly.

Ultimately, this book would be important simply by being the first monograph on black television in the seventies. However, Acham’s insightful class analysis offers fresh insights to programs that may be uncomfortable viewing for those with middle class sensibilities. This book is an important reminder that there is no monolithic black aesthetic, and that class interests must be kept in mind when evaluating a history of black criticism of black performance. By going beyond the positive/negative binary and exploring the possibilities of resistance, Acham has opened up a new discussion not only of black television in the black power era, but also of television’s representational economy. This economy is not simply raced, it is also classed. Without focusing extensively on reception, Acham is still able to stand up for audiences who loved these shows, even while the shows were denounced by critics. Undoubtedly, some of the program’s fans will read and enjoy this book, which is written in an accessible style making it appropriate for lay readers and undergraduates as well as scholars.

Notes

1. On the Real Side: Laughing, Lying and Signifying, the Underground Tradition of African American Humor