JUMP CUT

A

REVIEW OF CONTEMPORARY MEDIA

![]()

“Sugar Love”: an addiction to sugar points out one of the ways our exploitation of the natural environment may come back and “bite” us.

The Pack (2010): vampirism readily compares with consumption, a greed for resources, land, and blood.

Saint Germain Chronicles novel jacket: soil placed in a hidden compartment within the heels of vampires’ shoes.

Let the Right One In (2007): the connection between vampires and their native soil continues.

Blacula poster: Blaxsploitation vampire sub-genre.

Cronos (1993): immortality comes with a vampiric price for Jesus.

True Blood 2013: the modern television take on the vampire.

The Last Man on Earth: the first of the three adaptations of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend highlights environmental causes for vampirism.

Images from The Pack

A lonely road leads to La Spack Café.

Charlotte (Emilie Dequenne) at a roadside diner where motorcycle gang members taunt her.

Charlotte continues to believe she is developing a relationship with Max, the hitchhiker.

A vampiric result of environmental exploitation.

Earth bites back: vampires and the ecological roots of home

by Robin Murray and Joseph Heumann

Hurricane Sandy and its aftermath illustrate well the negative effects environmental exploitation can have on humanity. As the deadliest hurricane of 2012 and the second most costly storm in U. S. history, Sandy killed over 100 people (“Mapping Hurricane Sandy’s Deadly Toll”) and left thousands of residents homeless in New York, New Jersey, and New England. It was also at least “enhanced by global warming influences” (Trenberth), according to climatologists. This connection between human-caused climate change and the devastating hurricane that ravaged the East Coast highlights the irrevocable connection between humanity and the natural world.

In another way an August 2013 National Geographic article “Sugar Love” also demonstrates how our exploitation of the natural world may come back to bite us in unexpected but direct ways. An addiction to sugar spread by Western imperialism from the nineteenth century on has destroyed natural environments and enslaved indigenous populations from Hispaniola to Barbados, where, “you can see the legacies of sugar: the ruined mills, their wooden blades turning in the wind, marking time” (“Sugar Love” 87). According to the article, however, that destruction of environments and their people led to a sugar diet that destroys consumers. As Dr. Richard Johnson explains,

“It seems every time I study an illness and trace a path to the first cause, I find my way back to sugar” (87).

This same damaging connection of environmental degradation coming back to harm humans is explored in films from Mountaintop Removal Mining documentaries such as The Last Mountain (2012) to Post-Apocalyptic science fiction films like Tank Girl (1995), but it reaches terrifying levels in the horror genre.

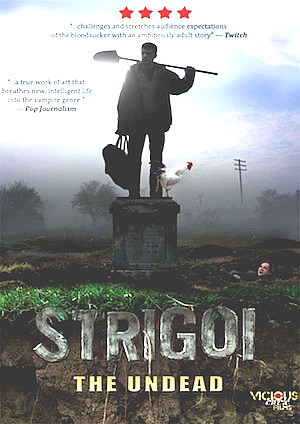

In the horror genre, a direct relation between environmental exploitation and destructive nature comes to the fore in the vampire film, when the living dead literally arise from the grave. In at least a few horror films, human desecration of the earth may create the very monsters that drink their blood. For example, the French black-comedy horror movie The Pack (2010) and the British/Romanian satire film Strigoi (2009) explicitly illustrate what might happen when an environment “bites back.” Although vampires have typically been associated with sexuality, power, evil and the Anti-Christ, fluid boundaries between humanity and the monstrous, and intimacy as conquest, in these two comic-horror films, The Pack and Strigoi, vampirism most readily matches consumption. A greed for resources, land, and blood separates humans from the natural world that provides their home. This separation from earth’s ecology and the home it represents has monstrous repercussions in these two films, transforming into horror the eco-trauma associated with a lost connection with nature and a shattered human ecology. Drawing on the work of early twentieth century human ecologist Ellen Swallow Richards and environmental psychologist Tina Amorok, we argue that these films amplify the real trauma humans experience when their earthly home is destroyed, illustrating the sometimes horrific effects environmental degradation may have on humanity. In The Pack and Strigoi, however, a damaged earth fights back, turning humans into vampires and ghouls, literal monsters who concretize monstrous treatment of the natural world and magnify the actual consequences of environmental exploitation.

|

|

| Strigoi (2009): a new exploration into the vampire genre that reconnects humans with the natural world that provides their home. | Dracula by Bram Stoker: sleeping in native soil highlights the novel’s primary theme. |

At least since the 1897 publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, integral to the vampire myth is the need to sleep in native soil. One of the novel’s narrators, real estate representative Jonathan Harker, remarks on the “earth placed in wooden boxes” (54) and sees while exploring Dracula’s castle that on “a pile of newly dug earth lay the Count!” (54). Later we learn that the Count has transported “fifty cases of common earth” (244) to his new home in England and that it is best to attack Dracula at certain times when he has “limited freedom” (258). A journal entry asserts,

“whereas he can do as he will within his limit, when he have his earth-home, his coffin-home, the place unhallowed, as we saw when he went to the grave of the suicide at Whitby, still at other times he can only change when the time has come” (258).

Such a connection between vampires and their native soil continues in filmic adaptations of the novel such as Nosferatu (1922), Dracula (1933), The Vampire Returns (1944), The Horror of Dracula (1958), Dracula Rises from the Grave (1967), and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992); in genre stretches such as the popular Van Helsing (2004, 2012) and Underworld (2003, 2006, 2009, 2012); the coming of age tale, Let the Right One In (2007); or the comedy, Vamps (2012). As in the Dracula novel, these vampire films underline the connection between soil and home, and consequently emphasize their link to ecology, literally the study of homes. Although some popular media representations of vampires eschew traditional vampire mythology altogether, many do include some version of native soil, even as in novelist Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Saint Germain series, placing it in a hidden compartment within the heels of vampires’ shoes.

Early in the novel Dracula, however, Count Dracula broaches another connection with native soil that extends beyond his need to become reinvigorated in his nation’s earth. When describing some of the “strange things of the preceding night” on the journey to his castle, Dracula connects soil with blood, declaring to Harker,

“there is hardly a foot of soil in all this region that has not been enriched by the blood of men, patriots or invaders” (25).

This direct relation between blood, soil, and vampires is overlooked in most representations of vampires in popular culture, despite its origin in Stoker’s novel. The Pack and Strigoi do examine these connections, highlighting the environmental underpinnings of the vampire myth in relation to a shattered ecology or home and illuminating the interdependence between human and nonhuman nature. The roots of that connection have, in fact, been theorized within the human ecology movement, which grew out of the work of Ellen Swallow Richards, a late 19th and early 20th century MIT chemist who defined human ecology in 1907 as

"the study of the surroundings of human beings and the effects they produce on the lives of men" (Sanitation in Daily Life v).

Destroying that human ecology, then, may lead to what contemporary clinical psychologist Tina Amorok calls an “eco-trauma of Being” (29). In both The Pack and Strigoi, vampires rather than eco-trauma result from this devastated home, soil desecrated by blood of war or exploitation of human and nonhuman nature. In The Pack and Strigoi, a mistreated earth bites back.

Reading the vampire

The vampire has long served as one of horror film’s most prevalent monsters—in silent versions of the Dracula novel and the successful stage play based on the novel in the 1920s, Universal’s great success in 1931 with Bela Lugosi in the lead, and Hammer Studio’s 1950s revisions of the Count’s narrative. Some sub-genres of vampire films have explored sexuality, while others have merged with other genres, including comedy, science fiction, and the Blaxploitation film. Love at First Bite (1979) and Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995) highlight the comic turn in the genre. Rabid (1976) and Red-Blooded American Girl (1990) illustrate a merging with science fiction, and Blacula (1972), Scream Blacula Scream (1973), and Ganja and Hess (1973) feature Blaxploitation vampires.

|

|

| Ellen Swallow Richards: the founder of the human ecology movement in the United States. | Men, Women, and Chainsaws book cover: gender criticism in media studies explores the horror genre. |

Academic research on the horror genre reflects the popularity of the vampire film and its multiple manifestations. Book-length explorations of the horror genre typically include references to the vampire film. The pioneering work of Noel Carroll, for example, examines representations of Dracula and other vampires in The Philosophy of Horror. Studies of pre-World War-II horror such as Reynold Humphries’ The Hollywood Horror Film, 1931-1941: Madness in a Social Landscape again discuss Dracula and the Dracula films in detail, as well as explore the vampire myth. Melvin E. Matthews, Jr.’s Fear Itself: Horror on Screen and in Reality During the Depression and World War II suggests that the horror cycle began with Dracula and Frankenstein (1931). Dracula is also included as one of the monsters George Ochoa examines in his Deformed and Destructive Beings.

Vampires are also examined in relation to their sub-genres. Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film explores Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987) from a gendered perspective. Bruce G. Hallenbeck examines comic vampire films such as Blood for Dracula (1974) and Love at First Bite. Monstrous Adaptations, an anthology focused on film adaptations of literary works also includes a study of the vampire myth in Brad O’Brien’s chapter, “Fulcanelli as a vampiric Frankenstein and Jesus as his vampiric monster: The Frankenstein and Dracula myths in Guillermo del Toro’s Cronos.” And an examination of the horror film as a cultural experience, Ian Conrich’s edited anthology, Horror Zone, includes explorations of Dracula and Van Helsing in multiple media. Yet none of these explorations address environmental concerns associated with the vampire.

The resurgence of the vampire in film, television, comic books, and other media has also encouraged a plethora of scholarly studies of media representations of a more contemporary vampire. Research exploring Buffy, the Vampire Slayer film and TV series, the Twilight films, and the True Blood HBO series provides a glimpse of the diverse lenses through which vampire identity is examined. Buffy, the Vampire Slayer resulted in a new area of research, “Buffy Studies,” which has prompted multiple volumes and conferences, including Lorna Jowett’s 2005 book, Sex and The Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan and an annual International Slayage Conference. The focus of research here, however, excludes ecocritical readings of the series, highlighting instead gender issues, aesthetics, family structure, and media and popular culture.

|

|

| Twilight Trilogy posters: young romamce meets the vampire in Twilight. | True Blood cast: the complicated soap-opera world of True Blood inspires multiple scholarly readings of the vampire. |

|

|

| Dark Shadows (2012): Tim Burton’s comic take on the popular vampire soap opera from the 1970s. | Near Dark (1987): Bigelow’s take on the new vampire nuclear family. A transfusion restores a young vampire to humanity late in the film. |

This exclusion of ecological readings continues in recent work addressing the Twilight series. Maggie Parke and Natalie Wilson’s edited volume, Theorizing Twilight: Critical Essays on What’s at Stake in a Post-Vampire World, for example, highlights the film adaptations as pop cultural artifact, explores the film adaptation series as fairy tale, romance, and coming of age narrative; and underscores the film series as texts open to readings from multiple critical perspectives, including patriarchy, white privilege, heteronormativity, rape culture, and religion. None of the chapters includes ecocritical readings of the films, despite their environmental leanings. Melissa A. Click’s edited volume, Bitten by Twilight: Youth Culture, Media and the Vampire Franchise

“gives crucial attention to the cultural, social, and economic aspects of the Twilight phenomenon. Building upon the work of feminist cultural scholars who examine girls’ and women’s relationships to the media, our overall goal in this collection is to examine Twilight’s themes, appeal, and cultural impact” (8).

Again the volume highlights theology, romantic love, gender and sexuality, race, and heteronormativity without a nod toward environmental issues broached by the novels and films.

True Blood studies also avoid exploring environmental issues. In “Lesbian Desires in the Vampire Subgenre: True Blood as a Platform for a Lesbian Discourse,”for example, Eve Dufour argues that True Blood addresses human fears of ‘the other’ and reveals the complexity of human sexualities and sexual desires. Maria Lindgren Leavenworth’s “‘What are you?’ Fear, desire, and disgust in the Southern Vampire Mysteries and True Blood” suggests that the sympathetic vampires in contemporary narratives

“are modeled on the early 19th-century Romantic instantations created by John Polidori and Lord Byron.”

In Brigid Cherry’s edited volume, True Blood: Investigating Vampires and Southern Gothic, Cherry explores True Blood as cult television. Part 1 of the volume centers on genre and style in the series, examining, for example, the Southern Gothic milieu in the series (see Caroline Ruddell and Brigid Cherry). Part 2 focuses on myths and meanings in the series, discussing the series as fairytale (Mikel J. Koven), a reworking of the Christ myth (Gregory Erickson), and a Minoritarian Romantic fable (Dennis Rothermel). Part 3 explores character and identity in the series, and part 4 highlights marketing and fandom associated with the series. None of this research, however, broaches environmental issues attached to vampires, the vampire genre, or the series in particular.

Environmental themes in vampire films

Although not often noted, both the Twilight films and the True Blood series are ripe for ecocritical readings. Most obviously in Twilight, the Cullen vampire family shuns human blood, claiming they are vegetarians because they drink only nonhuman blood. In True Blood, vampires are able to coexist with humans, at least initially, because a synthetic blood source has been developed. The cause of vampirism in these films is also sometimes tied to the natural world—a plague or virus. An early version of this “virus as origin of vampirism” theme can be found in The Last Man on Earth (1964), the first of at least three adaptations of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954), which also include The Omega Man (1971) and I Am Legend (2007). The three Blade films (1998, 2002, 2004) also play on this theme, as does the more recent Daybreakers (2009).

Other vampire films highlight the power of blood transfusion either as cause of vampirism or its solution. In Chan Wook-Park’s Thirst (2009), for example, Sang-hyun (Kang-ho Song), a priest working for a hospital, selflessly volunteers for a secret project intended to eradicate a deadly virus. However, the virus eventually takes over the priest. He nearly dies, but makes a miraculous recovery by an accidental transfusion of vampire blood. Dark Shadows (2012) uses this transfusion of vampire blood to comic effect. In Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987), on the other hand, a transfusion restores a young vampire to humanity.

The Pack: when earth fights back

Unlike most vampire films with environmental leanings, the comic-horror The Pack explicitly connects vampirism and its desire for blood with humanity’s exploitation of the natural world. The Pack highlights the sometimes horrific and blood-sucking consequences of mistreating the Earth in relation to exploitative mining techniques, which destroy both the land and its human laborers. Although the film begins as a road movie with illusory romantic possibilities between a lone driver, Charlotte (Émilie Dequenne) and a hitchhiker, Max (Benjamin Biolay), both genre and mood change when a drive ends at a café owned by Max’s mother, La Spack (Yolande Moreau), who hides a deadly secret that connects human and nonhuman nature. In The Pack, vampire miners and the slagheap that transformed them seek revenge.

Set around an abandoned post-industrial mine similar to the Lorraine mines of filmmaker Franck Richard’s childhood, The Pack connects vampirism to a ravaged Earth and a desecrated home. In The Pack, vampire-like ghouls are not only produced from a mine’s slagheap but also become an integral part of its byproducts, illustrating the interconnection between human and nonhuman ecologies. The specters arise only when they and the earth they inhabit are fed human blood. Unlike Strigoi, however, The Pack’s attempts at comedy conflict with any serious message the film may be making about mining, miners, and the environment they exploited.

The Pack fuses dark humor with multiple genres in its sometimes ineffective attempts to highlight that message. The opening scenes of The Pack provide little evidence of the grim ecological and human disaster revealed by the film. Instead the film begins as a road movie focused on a lone driver, Charlotte, who plans to go as far as her many CDs of music will allow. The film enters a simulated Wild West, however, when ridiculous outlaws riding motorcycles instead of horses chase Charlotte down a wind turbine-lined lane.

| Charlotte ignores the taunts of motorcycle gang. | Charlotte being pursued by motorcycle “cowboys.” |

| Max (Benjamin Biolay) waiting for a ride to La Spack café. | Charlotte stops to pick Max to protect herself from the gang. |

| While rifling through Charlotte’s wallet, Max discovers a torn photograph indicating she has no romantic connections. | The final road to La Spack café. |

The conventions of the comic road movie and Western turn monstrous when Charlotte picks up the hitchhiking Max to discourage the bikers. Music and setting changes reinforce this change with the introduction of Max, who is played by Benjamin Biolay and recognizable by most French and Belgian viewers as a singer, songwriter of songs such as “Bloodbath.” This song ties him to the horror genre and foreshadows The Pack’s blood-drinking ghouls, especially with the line, “He tells me, ‘You’re a vampire.’”

| Charlotte and Max enter the world of La Spack. | The first strange moment, as Charlotte watches a cellophane-wrapped boy staggering across the porch. |

| The unconscious victim of La Spack. | One of the macabre aquariums that decorates the interior of La Spack. |

Horror conventions are cemented when they reach La Spack, the dilapidated café at the end of a dark country lane where any efforts to infuse the narrative with comedy end. The tone grows even more foreboding when Max disappears into the café restroom and does not return. When Charlotte tries to find him behind a hidden door, La Spack assaults and captures her, locking her into one of the animal cages in the middle of a back room. In a makeshift torture chamber that takes Edgar Allen Poe to extremes, Charlotte and Tofu (Ian Fonteyn) are even force-fed their own blood to prepare them for their sacrifice to the vampires on the slagheap.

| The appearance of the motorcycle gang complicates Max and Charlotte’s conversation. | The gang begins their assault on Max and Charlotte, with videogames suggesting a Twilight Zone of horror to come. |

| Shotgun in hand, Madame La Spack (Yolande Moreau) exclaims “I’ll repaint my lino [leum] with your ball juice,” scaring them away from the café. | Puzzled by Max’s disappearance, Charlotte searches in the bathroom and discovers a hidden door. |

| Chinaski (Philippe Nahon), a retired sheriff, stops La Spack’s first assault on Charlotte. | Charlotte returns at night to search for signs of Max behind the hidden door. |

Connections between humanity and the earth are made explicit when this nightmare turns into eco-horror. At nightfall, the reason for Charlotte and Tofu’s blood diet is revealed. They have been prepared to feed monsters rising from the earth. Now helplessly weak, Charlotte and Tofu are flung into a coal car and pushed toward a slagheap where they are chained by their ankles. Cuts in their calves drip blood into the Earth, luring vampire ghouls dressed in mining clothes out of the soil. Eyeless, fanged and carrying mining tools, they seem to gasp for air but drink the dripping blood frantically, licking Charlotte’s leg and ripping off Tofu’s arm to drain his arteries. These monsters survive only in an earth fertilized with human blood.

| Charlotte discovers Max’s headband in the hidden passageway. | Charlotte finds herself a prisoner of La Spack and her son, Max. |

| Charlotte and Tofu strapped to a bizarre feeding machine invented by La Spack. | Chinaski discovers Charlotte’s hidden station wagon. |

| Charlotte is force-fed her own blood. | Madame La Spack drives her victims to the slagheap in a horse-drawn coal cart. |

| Blood in the soil attracts a vampire ghoul from beneath the earth. | Ghouls tear off Tofu’s arm for his blood. |

The source of these horrific monsters clearly connects human and nonhuman ecologies, however, moving the narrative beyond the extreme gore of the slagheap. As Max explains to Charlotte the next morning, his mother

“hasn’t always been like this. But when my brothers died, she went mad. The authorities would rather see them die in the mine than risk a firedamp explosion…. The village elders talked about a creature born of mud and the blood of the dead, miners who died underground. That always made us laugh. …. I think they dug too deep.”

Max continues talking as the scene changes to an external shot of power lines crossing a large field lined with winter trees, illustrating his claim, “My mother says the earth wants blood. And we can’t refuse it.” Charlotte’s discovery of a photo album of the La Spack family miners killed in a mining accident reinforces La Spack’s claim. On a page adjacent to photos of the La Spack’s now-dead sons, a newspaper clipping declares, “We raped the earth. It’s sending us monsters.”

| Vampire ghouls feed on the chained Charlotte and Tofu. | Max helps revive Charlotte and explains the source of the vampires, declaring, “My mother says the Earth wants blood. And we can’t refuse it.” |

| Chinaski continues his search for Charlotte by questioning La Spack. | La Spack’s album reveals the horrors of coal mining: “We raped the earth. It’s sending us monsters!” |

| Madame La Spack beats Chinaski at his own game. | Madame La Spack laughingly warns a gang member about his impending death. |

| Madame La Spack and the gang member share a drink before the vampire ghouls arise from the slagheap. | The vampire “miners” prepare to attack the mining shed. |

The horror reaches a climax at the slagheap during a battle between La Spack and a gang that includes Charlotte, Max, and the motorcycle club that followed Charlotte to the cafe. After a gruesome fight that leaves La Spack dead, her blood draining into the slagheap, the ghouls return, slaughtering everyone but Charlotte, who escapes the now-burning house through a window, exclaiming, “So the earth wants blood. I’ll give it some” as she shoots. When she reaches a field, however, the vampire ghouls rise up from the mist and follow her, feeding on her until the moon fades into morning.

The horror of this scene suggests a tragic end for Charlotte and Max and a resolution in favor of monstrous nature. Instead, Charlotte seems to survive, appropriating the now dead La Spack’s role, with Max resuming his own function as a handsome hitchhiker luring drivers in to feed the vampire ghouls they now protect. Quickly, however, the film switches from this dream sequence to a shot of Charlotte hanging on chains over the slagheap, where a vampire ghoul drinks her blood. The wind rocks the chain, and Charlotte’s blood drips into the soil. The sun comes up, and blood seems to cover the light with a hiss and red clouds. Bluegrass music ends the film, with the line “I’m down in that old coalmine,” lightening the frightening mood with perhaps ineffective humor.

| A classic way to die in a horror film—and open a door. | A ghoul backlit by the burning remains of the shed pursues Charlotte. |

| Charlotte is the lone survivor of the conflagration. | Charlotte as the new proprietor of the La Spack Café. |

| Max charms a new victim. | Charlotte awakens from the dream above the slagheap. |

This ending illustrates well the conflict between genre mixing and environmental message in the film. The appearance of the monstrous vampire rising from the slagheap reinforces the negative consequences associated with exploiting both human and nonhuman ecologies. But the film’s genre transformation from dreamlike resolution in the café to comic horror above the deserted coalmine dilutes this message, turning eco-horror into “an amusing hodgepodge” that is, as Jordan Mintzer of Variety states, “too uproariously modeled on every late-night classic under the sun to feel fresh or dramatically apt.” The movie may, as Mintzer asserts, soon “be unshouldered to rest alongside its home-video ancestry.”

Despite its weak ending and lack of originality, The Pack highlights the terrible consequences of eco-disasters associated with mining. The slagheap broaches not only the filmmaker’s childhood memories but also the real horrors of the mining industry and its exploitation of resources and labor. In Franck Richard’s own region of Lorraine, industrial medicine studies found an increased mortality from lung and stomach cancer in Lorraine iron miners (N. Chou, et al 1017). Coal mining in the region also had disastrous repercussions. According to a 1985 Los Angeles Times article, “an explosion [in February 1985] in a coal mine in France's eastern region of Lorraine killed 22 miners and injured about 100.” The article explains,

“The blast, 3,450 feet underground in the Forbach mine near the West German border, was thought to have been caused by fire damp, a gas given off by coal and constituted largely of methane. When it explodes, it immediately ignites coal dust nearby.”

The Pack turns these real instances of “monstrous nature” into biting horror.

To

top![]() Print

version

Print

version![]() JC 55

JC 55 ![]() Jump

Cut home

Jump

Cut home

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.